The Australian Forestry Council has endorsed the continuing practice of multiple-use management of public forests.

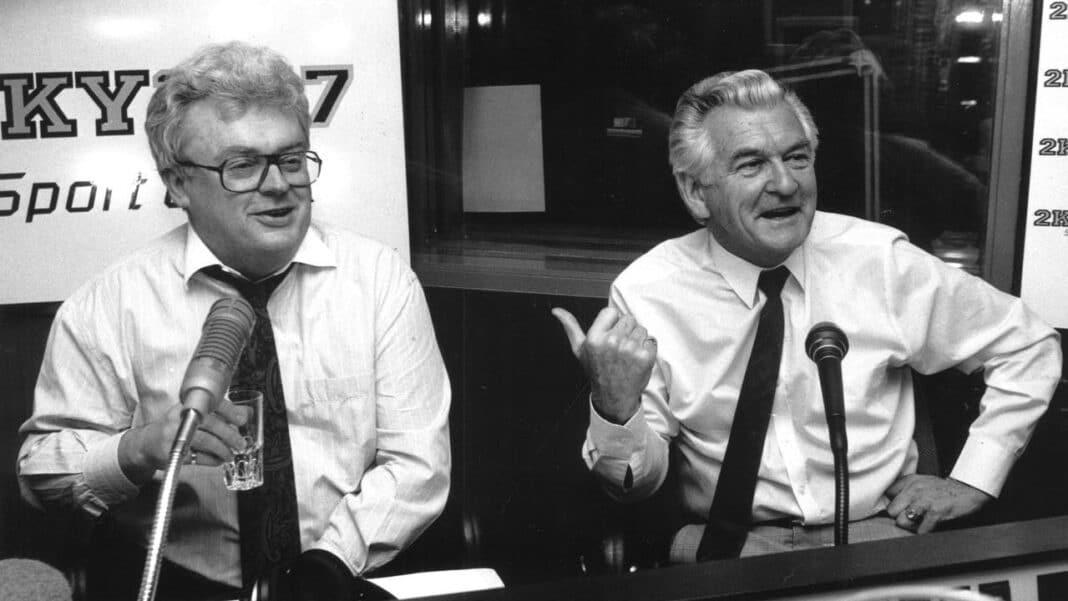

The Forestry Council comprises state and territory forestry ministers and is chaired by the Minister for Primary Industry John Kerin.

The council agreed at its meeting in Melbourne on June 6 that every effort should be made to achieve an acceptable balance between wood production activities and the conservation of the natural environment.

It agreed that preservation of scenic values, provision for recreational use, maintenance of wildlife, erosion control and water catchment protection were established goals in forest management.

Individual states are pursuing forest management policies which encompass those objectives, but the council plans to bring them together in a national forest policy statement.

The standing committee of the council is preparing a draft forest policy for consideration by the council at its next meeting.

The council expressed support for the draft national conservation strategy which will be considered shortly by a national conference.

The council will, however, seek major amendments to the background paper on forestry included in the strategy document.

In his first speech to the Australian Forestry Council since becoming a minister in the new Hawke government. Mr Kerin said national conservation strategy was concerned with striking a balance between the current utilisation of living natural resources and the conservation of those resources indefinitely into the future.

“I understand that states subscribe to the aims and objectives of the strategy but wish to see amendment of some of the text,” Mr Kerin said.

“The draft raises a plethora of issues – sustainable yield of wood; visual and recreational amenity; age structure of forests; soil fertility, erosion, and salinity; control burning; softwood versus native plantations; dieback; selective cutting; wood chipping; wildlife corridors and flora reserves; and more. All must be addressed.”

“Recently, community attention has been directed at the devastating effects of bushfires, not only in terms of personal loss but also the effect upon our forest resources.”

“Fires and forests form a combination which bears the closest scrutiny.”

“These and other issues will directly influence the direction of forestry in Australia. They need to be taken in hand by a coordinating body such as the Australian Forestry Council.”

Mr Kerin said forestry had had the traditional role of producing wood for commercial purposes.

The community increasingly demanded that forest development be tempered by a concern for the environment.

But it had not been widely recognised that foresters had been striving hard and successfully to operate within a framework that is conservation oriented.

Each state through its forest service has long been directly involved in development and maintenance of forests for purposes of soil conservation, wildlife preservation and protection of water catchments.

The Prime Minister had pledged a commitment ‘to develop with the states a massive national re-afforestation and tree regeneration program.

“It will be my task to cooperate with my colleague, Barry Cohen, the Minister for Home Affairs and Environment, to give effect to this commitment in as sensible a way as is possible,” Mr Kerin said.

“This council has a very significant role in the careful exploration of ways and means of establishing common ground on the wide range of conservation/preservation issues.

It must have a positive input into the national conservation strategy and the programs which will flow from it.”

Mr Kerin added: “The forest industries play an important part in the national economy.

Australia currently utilised some $3.2 billion worth of forest products annually, of which some $2.2 billion comes from local production.”

Editor’s note: Four years later, in 1987, the Hawke government had nominated roughly 9300 sq km of mostly wet tropical rainforest between Townsville and Cooktown for the UNESCO World Heritage list. It joined such illustrious company as the Great Barrier Reef, the Yellowstone National Park and the Grand Canyon.

The timber industry had tried to discount the influence of the environmental lobby, but it would be hard to believe the greenies’ catchcry of “Save the Rainforests” could fail to be a vote-winner in the southern concrete jungles.

Senator Graham Richardson, who, according to former Labor senator and judge James McClelland, would “not know the difference between a melaleuca and a marigold” went straight into the lion’s den after the election.

With media crews in tow, the new minister visited Ravenshoe, three hours’ drive south from Daintree. Ravenshoe (pop. 1200).

About 80 workers in the local timber mill were out in force to greet him. A well-televised scuffle ensued.

If accepted by the Paris committee, the listing would mean the end of logging within the Heritage boundaries – and drive the last nails into the coffin of the beleaguered north Queensland timber industry, already hit by diminishing Crown timber quotas and a spate of mill closures.

In what promised to be his last great battle before retirement, the Queensland Premier Sir Joh Bjelke-Petersen told timber industry workers that, if necessary, he would go to Paris himself to fight the listing.

The industry said it harvested less than 20% of the 850,000 hectares of rainforest in North Queensland on a 40-year “sustained yield” cycle that allows for regeneration.

However, the environmental lobby, led by the Tropical Rainforest Society of Queensland, said so-called “selective logging” of the rainforests was a failure.

In 1987, the industry’s timber quota was only about a quarter of the annual cut of a decade ago – proof, said environmentalists, that the rainforest was fast depleting, not regenerating.

And according to then conservation newcomer Senator Graham Richardson, the gross value of the industry was down to a mere $17 million annually.