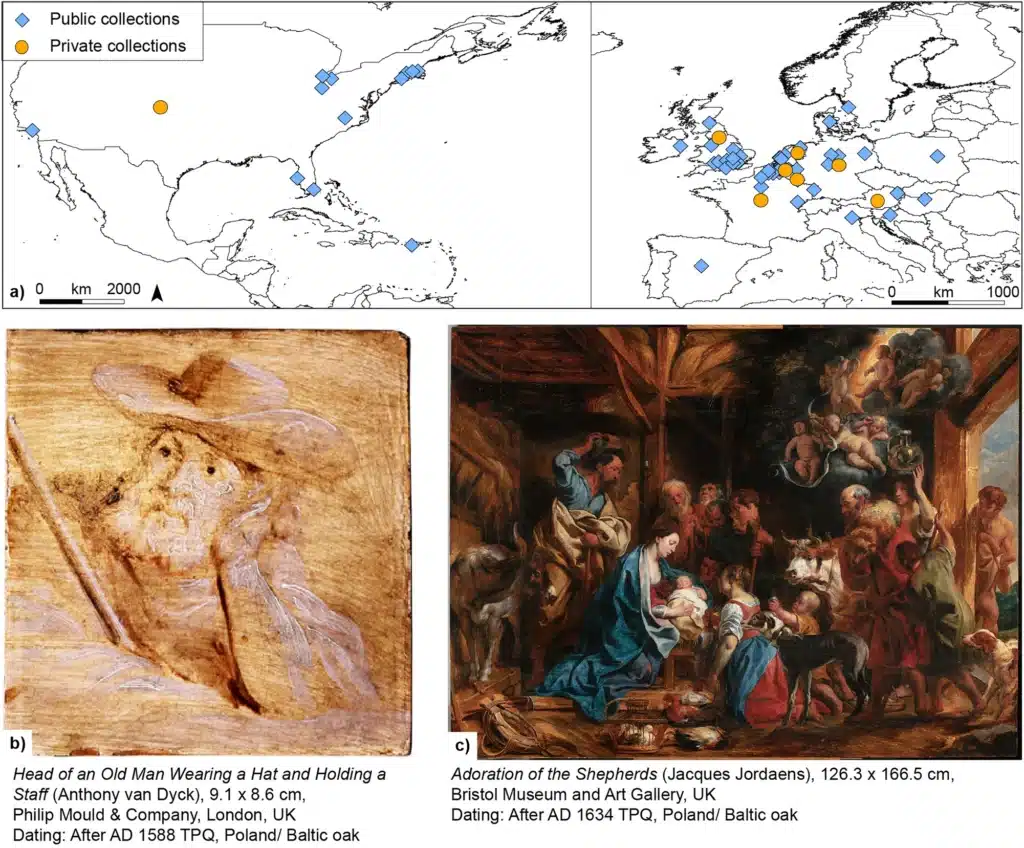

Global scientists are now using tree-ring dating to trace the origins of hundreds of the world’s most famous Renaissance-era paintings – with the study of 294 works from Jacques Jordaens and Sir Anthony van Dyck revealing insights into the booming 17th-century trade of European oak.

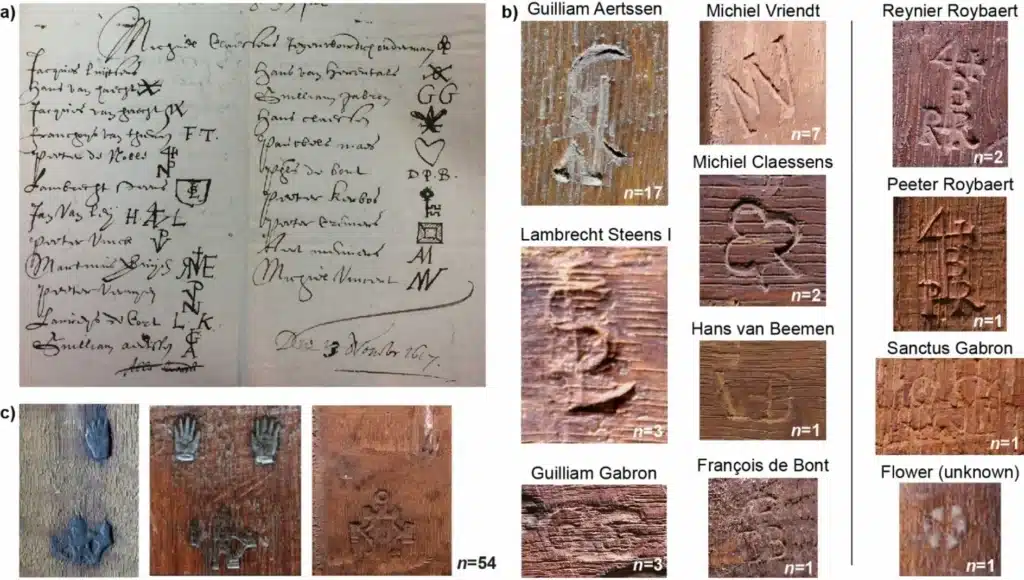

Published in Nature, the study used archival research, dendrochronology, and analysis of panel makers and guild marks on the paintings to gain key insights into the precise time of tree felling, the geographical provenance of the wood, and the panel makers patronised by the painters.

“Over 80% of the pieces were subject to a dendrochronological analysis, could be dated, and the results accorded well with the concomitant art historical assessment on authorship,” according to research led by Dr Andrew Seim, Chair of Forest Growth and Dendroecology at the University of Freiburg Institute of Forest Sciences, who said the quality of oak made it easy to date the timber’s origin.

“Besides an active and well-known Baltic timber trade, which provided over 71% of all the planks examined, straight-grained oak trees were also sourced from western Central Europe (20%). These planks, from the Baltic and the Ardennes region (France/Belgium), were used in three different paintings, likely cut apart from larger panels.”

Lead author, Dr Andrew Seim, on the importance of Renaissance-era art and the trade of European timbers.

According to Dr Seim, the period was a golden era for cultural expression with Antwerp, modern-day Belgium, the epicentre for a thriving art scene:

“Luxury goods like the arts, based on a high degree of specialisation and a more efficient production process, yielded relatively good profit margins, and paintings became popular export goods – providing context for great Flemish Baroque masters such as Peter Paul Rubens, Jacques Jordaens and Anthony van Dyck.”

“The favoured support for easel paintings in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries was oak panels, but canvas as support became prevalent as the latter century progressed,” the researchers said, adding that evidence is found in a letter sent by Rubens to Sir Dudley Carleton on 26 May 1618 regarding his The Expulsion of Hagar (71 × 102 cm):

‘It is done on a panel because small things are more successful on wood than on canvas, and being so small in size, it will be easy to transport.”

Peter Paul Rubens to Sir Dudley Carleton, 26 of May 1618.

Oak (Quercus spp.) was the preferred tree species for panels by painters in northern France, the Low Countries, western Germany, and England until the end of the seventeenth century. Wood Central understands that Panel makers and painters preferred slow-grown and old oak trees: “Because their narrow and regular tree rings and the straightness of the grain ensured high dimensional stability of the wooden support, thus preventing deformation of the planks.”

In addition, wood had a more regular and smoother surface than canvas, which not only allowed artists to render minute details but, more importantly, “pigments were better protected from discolouring and the preparation layer from becoming grey instead of white, because the wood blocked the oxygen in the atmosphere from intrusion from behind while the front was protected by varnish.”

According to the researchers, the period also coincided with a surge in construction timber from the mid-Medieval period (the tenth century) onward, resulting in “large-scale exploitation of old oak forests, starting in parts of western and central Europe,” resulting in “a shortage of locally available straight-grained and knot-free construction timber.”

“This led to the exploitation of forests in other regions of Europe, and thus, a largescale trade of construction timber developed,” the researchers said: “The timber trade in straight-grained oak trees from Poland and the other states on the Baltic Sea, generally referred to as the Poland/Baltic region, started in the mid-fourteenth century.”

As a result, “an active timber trade between Poland, the Baltic states, the Low Countries and England was established by the Kingdom of Sweden and Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in the fourteenth to eighteenth centuries.” And “since the timber was transported by sea, the felled oaks were split or sawn into planks or boards at the forest site or collection point, transported to the nearest port, and loaded onto ships.”

The researchers said the oak panels were “extremely costly, up to eight times more than canvasses of the same dimensions,” before adding that political instability led to the Guild of Saint Luke in Antwerp petitioning for the very law regulating the quality and size of panels for painters.

Dr Seim said the research also proves that “primary forests still existed in Western and Central Europe in the seventeenth century even though this region was densely populated and highly urbanised.”

“Tracing the origin of mature oaks in the material of artworks requires a large data pool of regional and local reference chronologies, combined with further archival research on suitable forest stands and rafting history to identify the exact location of such old-grown oak forests.”

For more information: Seim, A., Edvardsson, J., Daly, A. et al. Timber trade in 17th-century Europe: different wood sources for artworks of Flemish painters. Sci Rep 14, 18216 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68641-y.