Cities are increasingly experiencing dangerous heat as urban concrete and asphalt amplify rising temperatures. And whilst tree-planting programs are a popular, nature-based way to cool cities, these initiatives have been primarily based on guesswork and extrapolation.

However, that could all change thanks to a new study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, which offers a new tool for urban planners and decision-makers to set more specific, science-based city-wide greening goals.

The study is led by Jia Wang, Weiqi Zhou, and Yuguo Qian at the Chinese Academy of Sciences and co-authored by Steward Pickett, an urban ecologist at Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies.

“Trees offer many benefits to cities, and cooling is one of them,” Mr Pickett explained. “Trees are good at cooling because they pump a lot of water from the ground into the air, and when that water evaporates at the leaf surface, it absorbs a vast amount of heat. That’s just the physics of evaporation. The shade provided by trees also helps with cooling.”

To date, most studies measuring the cooling effects of urban trees focus on the hyperlocal level, such as on a particular street or neighbourhood. When the urban tree canopy expands by 1%, nearby temperatures may decrease by 0.04 to 0.57 degrees Celsius.

“That’s valuable, but planners and decision-makers are thinking about the whole city,” said Mr Pickett. “They’re asking, “How much tree canopy do we need for the whole city? What happens when we scale it up?” And that information hasn’t been available.”

It wasn’t clear whether the fine-scale results could be extrapolated to the city scale. So, the researchers set out to determine how trees’ cooling efficiency—the temperature reduction associated with a 1% increase in urban tree canopy—changes across larger areas.

The team analysed satellite imagery and temperature data from four cities with very different climates: Beijing and Shenzhen in China and Baltimore and Sacramento in the US. Baltimore and Beijing are temperate, Shenzhen is subtropical, and Sacramento is in a Mediterranean climate zone.

First, they divided each city into pixels approximately the size of a city block. For each pixel, they measured the land surface temperature and the amount of ground covered by trees.

Then, they ran the same analyses across increasingly large sections of each city, spanning the neighbourhood level, city level, and beyond. Finally, they calculated how the mathematical relationship between greenery and temperature—the cooling efficiency—changed at different scales.

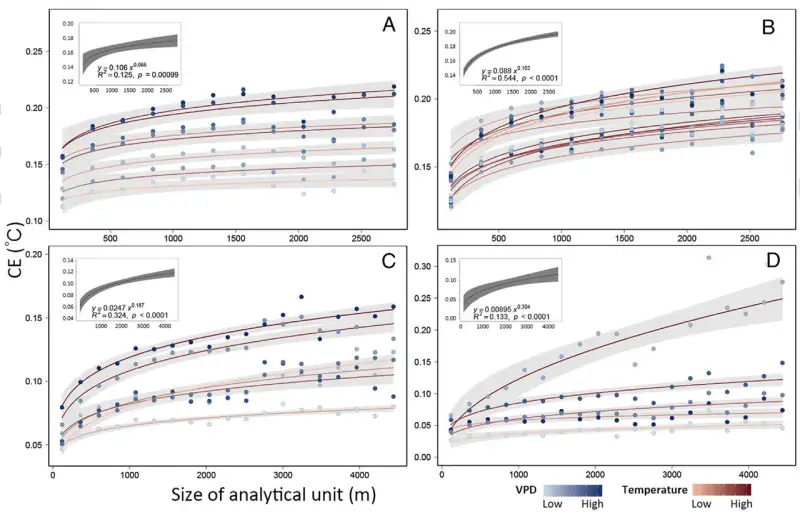

The relationship between area (“size of the analytical unit”) and cooling efficiency (“CE”)—the temperature reduction associated with a 1% increase in urban tree canopy—follows a statistical power law rather than a linear relationship.

As the area size initially increases, urban planners can get more bang for their buck—each 1% increase in tree canopy cover offers additional cooling benefits. The line tends to level out at larger and larger scales. The relationship holds across four cities:

Overall, the team discovered that urban trees’ cooling efficiency increased at larger scales but slower at larger unit sizes. In Beijing, for example, a 1% increase in the canopy at the block level decreases the temperature by about 0.06 degrees.

In contrast, a 1% increase in the canopy at the city level could decrease the temperature by about 0.18 degrees. The additional benefit at larger scales seems to come from including large groups of trees with a larger cooling capacity.

With greater clarity about the relationships between area, tree canopy cover, and cooling effects, the paper makes it possible to predict cooling effects at the whole-city scale, offering a valuable tool for managers to set urban tree canopy goals to reduce extreme heat.

Co-author Weiqi Zhou notes, “We found that cooling efficiency follows a power law across scales—from as small as 120 by 120 meters to as large as regions covering the entire city. The relationship holds across all four studied cities in very different climates. This suggests that it could be used to predict the amount of additional tree cover needed to achieve specific heat mitigation and climate adaptation goals in cities worldwide.”

For example, the authors estimate that the city of Baltimore could reduce land surface temperatures by 0.23°C if they increased tree canopy by 1%. To achieve 1.5°C of cooling, they would need to increase tree canopy cover by 6.39%.

While the paper provides essential information for municipal decision-making, Pickett cautions that urban planners may also need to work at smaller scales to ensure that urban trees—and their potential benefits—are distributed equitably across the city and with community buy-in.

“This paper doesn’t tell you where to put the trees,” said Pickett. “That’s another sort of analysis involving much more social information and engagement with communities or individual property owners.”

Pickett suggested that the next steps could include broadening the analysis to include other cities with different climates and examining how well this nature-based solution will work in the future as climate change makes some areas hotter and drier.

More information: Jia Wang et al, A scaling law for predicting urban trees canopy cooling efficiency, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2024). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2401210121

Journal information: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences