As Ukraine looks to recover its “scorched earth forests”, home to the largest number of landmines, South Korea could provide the war-torn country with a much-needed pathway to economic prosperity via long-term investment in reforestation and value-added manufacturing.

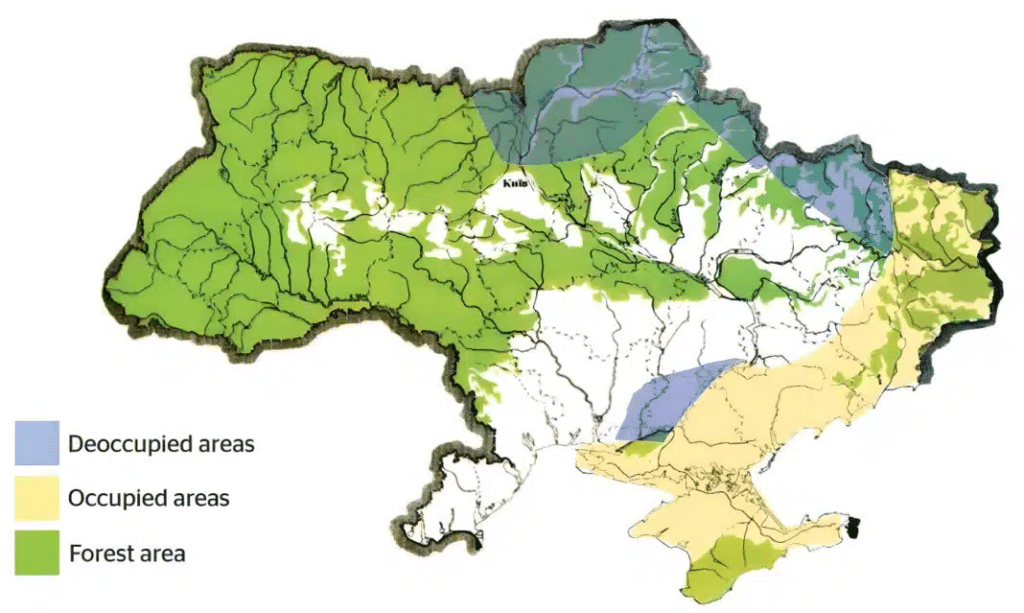

To date, more than 3.5 million hectares of forests have been destroyed by Russia’s military occupation of Ukraine and Crimea, amounting to 1 million hectares of areas designated for FSC and PEFC certification. With heavy disturbance in aboveground ecosystems, soils and water systems have a generational impact on forest health.

Ukraine has long been a sleeping giant in global forest products, with Forest Europe and various non-government organisations pushing for global governments and financial institutions to provide much-needed support to “build back better.”

And like Ukraine, South Korea’s forests – once home to one of the most vibrant and productive forests on earth – were effectively razed to the ground after the 1910-45 Japanese occupation, followed by the 1950-53 Korean War. This devastation led to social and environmental problems, including a lack of fuel, severe floods and droughts.

In fact, by the end of the Korean War, more than 30% of the previously forested land in South Korea was depleted or wholly denuded.

Fast forward to 2024, and the country is now spearheading the global “green transition”, with one of the highest forest cover in the world (65% – double the global average) and boosting a manufacturing industry amongst the most sophisticated on earth; both instrumental in driving the country’s economic miracle from the 1970s onward.

From 1961 to 1996, the country effectively wrote the rule book for sustainable economic development, rapidly industrialising whilst investing extensively in growing a “green economy.”

Today, South Korea is one of the largest importers of timbers in global markets, creating a large plywood and veneer manufacturing market, consumed by domestic markets and competing with China, India, and Indonesia as “value-added products” in global markets.

South Korea’s response to deforestation and subsequent investment in reforestation began in the 1960s after the military junta pitched its wagon with forest management, critical for improving the people’s livelihood.

Without many capital resources or technical skills, the junta targeted three critical areas for rapid improvement.

- Address the sources of deforestation.

- Empower the agents of change.

- Establish a system of accountability.

Supported by loans from the US Agency for International Development and the World Bank and with aid from European experts, it developed domestic fuel sources – the primary source of local deforestation, boosting its transportation infrastructure to create supply chains for forest products.

By the early 1970s, the newly established Korea Forest Service (KFS) was driving extensive reforestation initiatives – which continue to this day – with more than 11 billion trees planted in the period leading up to 2008 and with the KFS committing to plant a further 3 billion trees over the next 30 years to replenish carbon stocks.

In arguably the best orchestrated and publicly cohesive reforestation event in world history, South Korea spent the 1970s and 1980s “turning bare land into a green nation” in what then-President Park Chung-hee declared was an “act of patriotism.”

Reforestation provided the predominantly agricultural economy with much-needed domestic timber supply throughout the 1970s and 1980s. As imports replaced domestically grown timbers (and South Korea is now looking to rebuild its plantation estate), it has also provided extensive carbon banks to help transition to carbon neutrality.

Now, South Korea is using its forest expertise to wield geopolitical power across the world. Using the KFC, amongst the best-resourced forest services in the world, it has been busy securing global partnerships with more than 39 forest producers – starting with Indonesia but including Australia, NZ, Canada, Japan, Vietnam and Russia.

Its latest partners include East Timor, with a deal struck in Soel last year, with the focus of its partnerships not only helping “boost the global supply of timber” but, more importantly, tackling climate change and “increasing the diversity of damaged ecosystems and tackling wildfires.”

Whether Ukraine can follow South Korea’s example remains to be seen. However, with a central authority, strong policy settings and international support, it could provide a beacon of hope for a country about to celebrate the second anniversary of the Russian invasion.