The land-sharing-sparing debate is alive and well, with climate change proponents pushing public think tanks and bureaucratic committees to lead to a single focus on land-sharing.

Land sharing means just what the words suggest. Arable land is a scarce and finite resource. Rather than lock up and leave (land sparing), this resource must be managed and shared. Native timber is a front-line issue in the land sharing or sparing debate.

However, the land-sharing-sparing debate presents a conundrum.

With an ever-increasing population, there is a need to acknowledge the balance between the need for sustainable human habitation on the planet and the protection of the Environment and biodiversity. This tension is real but not evident in legislation on climate change, carbon, and biodiversity, which is driven by foreign treaty obligations.

‘The land sharing-sparing framework arose in literature around discussions about biodiversity conservation-agricultural production trade-offs but has been increasingly applied to biodiversity conservation-forestry trade-offs. In forestry, extensive management in native forests with selective harvesting is an example of land sharing.

In this article, we look at the issues related to native forestry or hardwood production in New South Wales (however, the same could equally apply to Queensland, where the $700m hardwood industry was “stabbed in the back” by the State Government).

In New South Wales, a body of highly effective not-for-profit environmental organisations are seeking to end all native forestry within Australia; the National Parks of NSW, the EPA NSW, the NSW Minister of the Environment, and the National Parks Association of NSW are working toward the same goal—to end forestry in State Forests.

Polling – public perception and manipulation.

In August, the Australian Institute surveyed 1500 Australians and found that 69% supported ending the hardwood industry (native forestry harvesting) in New South Wales and Tasmania. This was after the respondents were told that the governments of Victoria and Western Australia would end harvesting at the end of 2023.

Just how much influence this approach had on the overall results is indicated by the SollzNow October 2023 survey cited below…

In March, Wood Central reported polling industry commentary that suggested that the polling result was ‘framed’ and, therefore, unreliable. The question put was about ‘native logging,’ which, as it happens, is not what happens in state-productive forests.

The word ‘logging’ ignores all other issues that occur in well-run forests. It is now a word charged with emotions rather than facts.

Had the question been posed, ‘Do you support sustainable harvesting and management of native forests?’, the answer would have been much like the result of the StollzNow research. The land-sparing advocates continually use emotive slogans that are misrepresentative and misleading to falsely present the issues.

At the same time as the Australian Institute was polling, StollzNow, Sydney, undertook ‘social licence’ research in NSW. They researched whether the NSW community gave its authority to the native forestry industry to operate on the state’s North coast. The research worked with ten different focus groups from Sydney and Northern NSW, with the study commissioned by the North East NSW Forestry Hub, funded by the Commonwealth Government.

The results presented the following…

With the ‘don’t know’ response removed, ‘The social licence to operate’ returned – 86% considered native harvesting a legitimate industry, 68% saw native forest harvesting as an ethical industry, and 67% said,

‘I trust the native timber industry’.

There were other interesting findings – there are more important issues than native forestry. People liked wood.

The primary forest concerns were fires, loss of native habitat, and land clearing for housing developments and farms. The ‘good’ issues included the fact that forest products were renewable and that Australia should be using more Australian products. The bad issues included the aftermath of a harvesting operation, which was confronting. There were native animals and biodiversity-focused concerns.

Parliamentary elections have suggested that a consistent 10% of the population is in a non-negotiable Green-environment portion. StollzNow pointed to this fact as well. This 10% are well organised on land sparing. The other 90% are not at all focused on the issue of land sharing. But the SollzNow work in October 2023 put ‘cost of living’ as the main issue.

Why do land-sparing advocates use emotive language and misrepresentations?

One explanation is money, or rather, the eliciting of donations.

The Australian and Not-for-Profit Charities Commission website shows how well-funded the environmental movement is. Many environmental groups fall into this governance sector. An example is the WWF in Australia (WWF-A), which had an annual income of $70M on its last ACNC return.

The Minutes of the 42nd AGM for the World-Wide Fund (WFF-A) for Nature Australia, held on 24 November 2020, reveal that funds from their Bushfire Fund were used for conservation. It was reported that in FY 20, there was an increase of $5.9M in expenditure for conservation expenses to $23.5M.

Fundraising expenses were $17M higher than in FY19 due to this work for acquiring new donors and campaigns related to the bushfire appeals. Significantly, WWF-A’s Bushfire Fund accounted for $14M in FY20. Based on commitments, it was reported that it was expected to grow to $45M.

Minutes of the 44th AGM for the World-Wide Fund for Nature Australia held on 24 November 2022 reveal the CEO, Mr Dermot O’Gorman, reporting:

“Off the back of bushfires, WWF-A developed a campaign and ambitious agenda to regenerate Australia. To date, this effort has raised almost $190M (towards a target of $300M) and funded conservation impact across WWF-A’s on-ground work, market-based transformation and advocacy portfolio. The WWF is committed to double down on this effort and drive the ambition needed to bend the curve for climate and biodiversity.”

The WWF and many environmental groups seek land sharing rather than land sharing. This approach is absolutist without any bending, and their current focus is the closure of Australia’s hardwood industry, with Australian agriculture next in line.

Land sharing – Uses of hardwood in Australia

The distinguishing thing about hardwood is that, as its name suggests, it is the hardest timber in the world. Its molecular and growth features make it extremely strong, comparatively stronger than steel. Timber products produced from native hardwood range from high-value, such as cladding (which comes from wood residue), to low-value, such as sawdust. For example, the Timber NSW membership comprises 35 different products.

Housing

Hardwood was once used for the frames of houses. Softwood is now used because it can be nailed. Hardwood must be screwed. However, this does not eliminate the role of hardwood in housing construction. It is used for floorboards, wooden features, decking, and window frames.

Removing local hardwood from housing construction means it will be imported at a greater cost. Substitutes such as plastic decking also have a greater cost.

Hardwood house frames were constructed in Australia on a refabricated means. This was to assist with construction because of the hardness of the timber. Hardwood house frames have great strength and can withstand climatic events from storms to floods whereas softwood frames are shattered.

These issues are cost of living concerns.

There are also concerns for a decarbonized economy. Internationally, the construction industry is responsible for a large fraction of greenhouse gas emissions, with concrete and steel production representing about 10% of total global emissions. As a result, there is strong evidence that wood products have lower lifecycle carbon emissions when compared to products made from non-renewable or emissions-intensive materials such as steel, concrete, plastic, brick, and carpet.

Power Poles

The ubiquitous timber power poles that line the streets and roads of Australia are almost invisible as they have always been there. They carry the current that powers homes, lights streets, oval lights, play grounds, and our communication towers and mobile phones.

In Australia, there are eleven million electricity customer connections. The Australian electricity networks extend 900,180 kilometres (that’s long enough to circle the equator 23 times). An estimated 86% of the poles are hardwood poles, which is just under nine hundred thousand million hardwood poles.

Timber power poles are selectively harvested from regrowth or working forests. Most hardwood pole sizes required by energy networks can be grown within 15-35 years and are known to last for over 60 years.

In addition, timber poles have a price advantage over alternate materials and have flexibility in use, natural insulation, compatibility with the existing infrastructure, carbon cycling, and sustainability over other materials like concrete, steel, and fibreglass.

The Australian Energy Regulator’s on-line 2021 Report acknowledges that:

‘Electricity network charges make up 40 – 50% of a residential customer’s energy bill in 2020-21. Distribution networks account for the majority of costs (73-78 %), with transmission network costs (up to 21%) and metering costs making up the balance. (page 147)

The Australian Energy Regulator’s online 2021 report does not appear to consider the cessation of the native forestry industry.

If timber poles were unavailable because the native forestry industry was to close down, new poles would be made of steel, fibreglass, or concrete. Concrete poles cost 2x to 3x greater than timber, while steel costs 3x to 5x higher.

And even then, this does not consider the issue of carbon sequestration, as timber poles are carbon-affixing sustainable units. The alternative utility steel, fibreglass, and concrete poles are not carbon-affixing sustainable units like timber.

This cost will increase the network operators’ operating expenditures (See ‘State of the energy market 2021’, Chapter 3, Electricity Markets, P. 134). This operating expense is a direct cost and does not consider the climate or energy costs of producing concrete or steel poles.

This is a cost-of-living issue for every Australian.

The NSW Minister for the Environment’s budget estimates on 7 March 2024 clearly showed that she had no idea of the impact of removing wooden power poles from the community.

The policy of using plantation woods for current hardwood power poles is unrealistic. A major electricity utility has recently contracted for ‘fire resistant poles’ – available – following the 2019 fires in urban areas. Tallowwood, iron bark and blue gum are not found in plantations.

Pallets

There is a good reason why pallets in the logistics industry are made of hardwood worldwide. The hardwood is stronger than any other replacement substance, which is plastic, and it does not spark!

Pushing, sliding, or dragging plastic over and along metal surfaces, such as the trays of transport trucks or the floor of metal containers, will create static electricity. Wood is far more efficient than plastic.

Victoria was the primary source of hardwood wooden pallets in Australia. The timber used was not high-grade quality logs but large off-cuts and small logs. Whilst difficult to verify, information obtained for this article confirms that at the time of the announcement of the closure of the Victorian hardwood industry, there was a shortage of 800,000 – 1,000,000,000 pallets from the volume of normal production.

This was due to a timber shortage.

What is known is that the production of native forestry products from Victorian native forests has now stopped – which means that pallet production from Victorian hardwood has ceased. What is known is that hardwood pallets are essential to the continued operation of all industries engaged with the logistical industry for the delivery and receipt of goods.

During COVID, the shortage of pallets was so severe that one enterprising NSW sawmill engaged in pallet repair to try and meet the demand.

More recently, CHEP, the leading pallet supplier in Australia and owned by Brambles, was so concerned about the future supply of hardwood that they conducted an industry survey to gauge the threat to hardwood supply. Previously, concerns were silenced because the major retailers who use pallets, Coles, Woolworths, and Bunnings, should not be spooked by what was materializing with hardwood pallet supplies.

There is no ready substitute for hardwood pallets; any substitute will cost more. Plastic pallets are not carbon zero. This is a cost-of-living issue for every Australian.

Railway sleepers

Hardwood timber has remarkable flexibility due to its molecular structure, which allows it to take great stresses without breaking. NSW produces Grade 1 sleepers, which are now in demand from Victoria, WA, and across NSW.

Concrete sleepers are now in greater use, but the interval for replacement is much longer than hardwood sleepers, as they crack due to the stress under which they are placed. Concrete sleepers are by no means net zero, unlike hardwood sleepers. It appears that they are no ideal substitute for hardwood sleepers.

Wharf timbers and Mine timbers.

Recent newspaper reports advised that Sydney Harbour’s wharves are in disrepair. The timbers used on marine installations are turpentine, a eucalyptus found in native forests. This hardwood is particularly resistant to water damage due to the timber’s oils. It has a much better endurance in a marine environment. There is no real substitute for quality fit for purpose, other substitutes, and carbon neutrality.

Mining timbers are also hardwood and essential to the operation of mines due to their strength and the fact that, unlike metal and concrete, timber does not spark if struck.

Carbon neutral

The average person is being bombarded with news reports and meta entries from not-for-profit environmental groups lauding that native forest trees are more efficient as carbon sequestration items than growing trees in the forest. The problem with this position is that the validity of such a stance has to do with the methodology.

The Kyoto methodology does not account for carbon storage in landfills, avoided carbon emissions embodied in substitutes (e.g., steel, concrete, and wood from unsustainability-managed forests), and avoided fossil fuel emissions by using biomass energy (UNFCCC, 2008; IPCC, 2013).

The Australian National Carbon Accounting System, however, does account for the carbon stored in landfills, avoided emissions in substitutes, and avoided fuel consumption (Australian Government Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources 2020, 2021).

A life cycle assessment (LCA) considers all relevant carbon emissions and removals. The Australian environmental movement, seeking an end to native forestry operations, rejects this methodology. Yet, it is perhaps the best approximation for atmospheric impacts.

In his article, which Wood Central covered last year, Tyson Venn outlines four main carbon benefits of forests managed for timber.

- Firstly, harvested logs can be transformed into wood products that store carbon off-site for many decades while freeing up growing space within forests for further carbon sequestration. Indeed, it is possible to achieve growth in the caron life cycle of one harvested tree by three more from the same place in the native forest.

- Secondly, wood products from sustainably managed forests can displace high embodied carbon substitutes.

- Thirdly, fibre and residue products from silviculture practices can meet energy needs from recycled biosphere carbon instead of fossil fuels. This is controversial in NSW, with the Department for the Environment’s policies allegedly based on statutory provisions but clearly open to challenge.

- Finally, ‘there are climate risk mitigation benefits of having a diversified portfolio of forest carbon sinks through land sharing, including wood products, displaced substitute products, and energy, which are less susceptible to disturbances such as wildfires and cyclones than carbon stored on-site only via land sparing’.

Environmentalists and idealogues dismiss this issue within the Federal and State bureaucracies, who argue:

‘My road or the highway’

Imported timber

Importing timber will come from countries with inferior harvesting standards. As a result, Australia is now exploiting forests in third-world countries. All these responses in the focus groups point to features of the hardwood industry in Australia.

It is worthwhile to walk through some of these pointers.

Australia’s imported timber is now valued at $6.9 billion, with a $4.1 billion timber trade deficit in the sixth most forested country in the world!

This increase has been largely met by developing countries— “illegal logging is responsible for up to 30% of global timber production, and 50% to 90% of harvesting in many tropical countries.”

Demand for this timber is likely to grow. One month after the September 2021 Western Australian announcement of the native forest production shutdown, local furniture manufacturers sought to substitute timber from Indonesia.

In addition, fumigation is necessary to import timber products into Australia.

There is a real biosecurity risk with imported timber if fumigation certification is falsified. Biodiversity issues have arisen with the Scientific Committee of the EPBC Act, where ‘scrub eucalypt’ is classified as endangered due to an invasive species, ‘ myrtle rust’. There is a concern that this species will kill swathes of native forests and, therefore, native habitats. There is evidence of ‘crowding out’ of regeneration of killed species.

Invasive species are the most common pressure on species listed under the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, affecting 82% of threatened taxa in Australia in 2018. (Australia State of the Environment 2021).

A Federal Government website lists nine invasive species that can enter Australia through wood products. The damage they can achieve varies from the destruction of hardwood and/or softwood forests to structural damage to timber products.

Phytophthora quarantine area – Barrington Tops National Park

Phytophthora is a mould that causes plant dieback. It’s been found on the plateau in Barrington Tops National Park, predominantly on the Watergauge trail between Beean Beean and Black Swamp. The affected area is under quarantine, and visitors are not allowed access.

Also called phytophthora dieback, root rot, or cinnamon fungus, once it’s established, it can’t be eradicated, and there’s no cure. It’s one of Australia’s top 100 invasive species impacting biodiversity and is listed as a key threatening process under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Act 1999.

There is an irony here, given the unbending position of the Australian environmental movement to land sparing, that cessation of native forest production in working forests raises serious and greater biodiversity risks to the Australian native bush. The view of people in the timber industry, from foresters to merchants, is that, unfortunately, invasive species will arrive whilst wood is imported. It is just when and what destruction will occur to native habitat.

Illegal logging is the largest environmental crime by value in the world. The Australian Government’s legislation, the Illegal Logging Prohibition Act 2012, defines the meaning of ‘illegal logging’ as timber harvested outside the laws of the country of origin.

However, this sets a low bar. The higher bar is the maintenance of a sovereign hardwood industry within Australia. It is also a bar for the protection of the Australian fauna and flora.

There is also the matter of country of origin. Embargo Russian timber is finding its way through China. If a manufactured veneer product is out of China, where is its origin? China does not have a lot of forests.

Australians expect forestry standards and rules such as those contained in NSW statutes, the Forestry Act 2012, and delegated legislation, the Coastal Integrated Forestry Operation Approval (CIOFA), which is over 300 pages of prescriptive measures.

Imported timber does not match these standards and rules as they are the most prescriptive in the world.

Myths put forward by land spares.

Environmental not-for-profits opposed to native forestry repeated the following myths when seeking donations.

“Native forestry is deforestation.”

A glance at the CIOFA will reveal the myth. Native forestry in NSW runs at a loss. The 2023 Annual Report of the Forestry Corporation of NSW (FCNSW) will reveal the falsehood here. Native forestry operations do run at a profit. Timber from native forestry is used in the cheapest possible uses. Published figures from 2019 advised that the average price of sawn Australian hardwood is $1254/m3, while the average price of sawn Australian plantation softwood is about $391/m3.

Native forestry operations cause water quality issues in river systems.

In NSW, there is a very high level of catchment protection. The CIOFA has conditions and protocols for erosion controls that are strictly enforced. There are over 2000 operating conditions, with over a hundred relating specifically to soil and water protection.

The biggest issue impacting water quantity and quality is bushfires.

Wildfires’ effect on water quality and quantity is tenfold greater than that of any other forest disturbance. Native forests should be left untouched as carbon stores. This argument uses the Kyoto methodology rather than the whole life cycle methodology.

Tyron Venn writes: The International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has long argued that forest management aimed at maintaining or increasing forest carbon stock while producing an annual sustained timber, fibre and energy yield will generate the largest sustained climate risk mitigation benefit from forests.

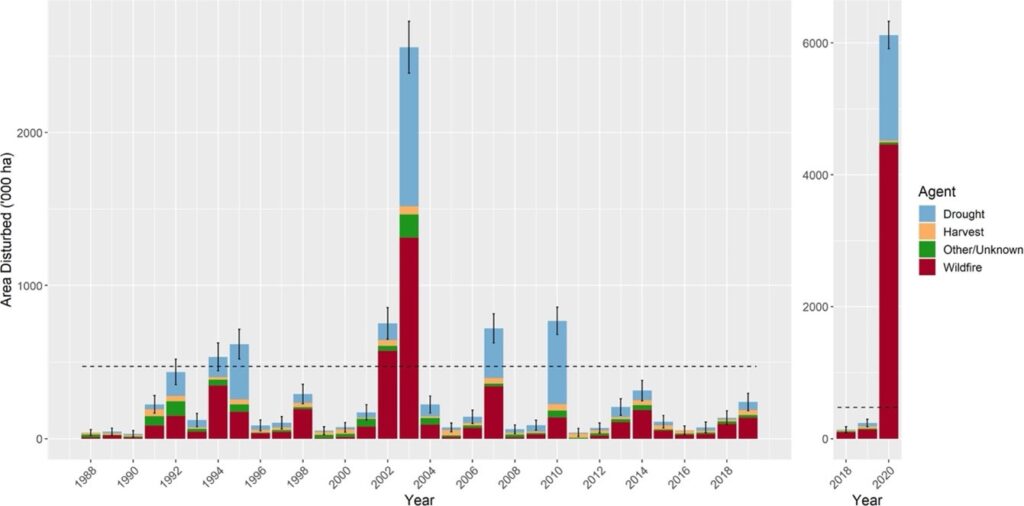

Forest Disturbance

Pasted below is a graph that shows the source of forest disturbance in NSW RFA forests over the last 32 years. Note the small impact of harvesting when compared to wildfires and drought. It comes from a paper by Hislop et al. (2021):

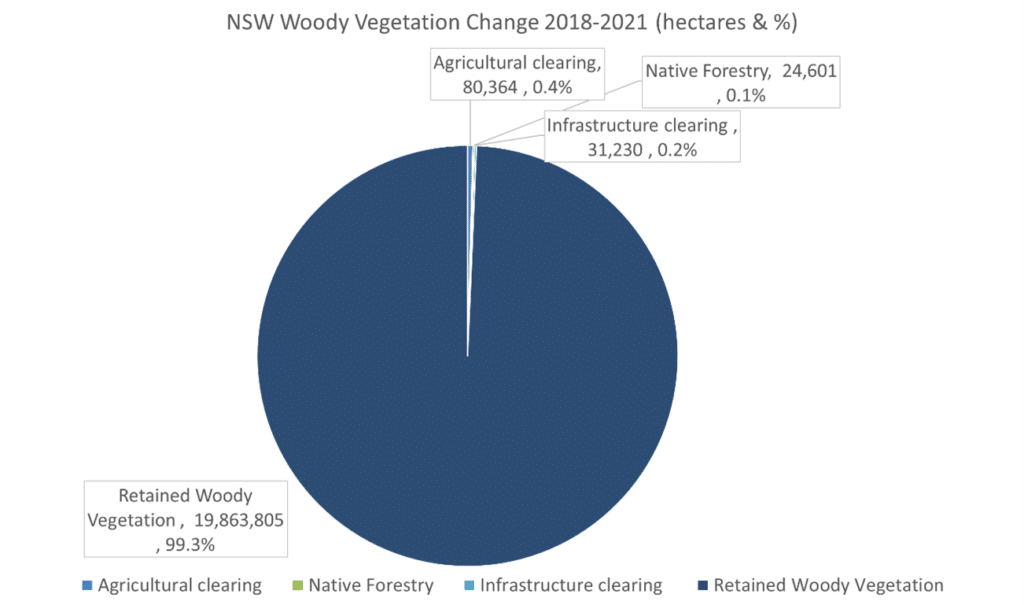

The next graph on NSW statewide vegetation clearing is clear in what it shows:

NSW Environment & Heritage woody vegetation monitoring data shows that over the four years 2018-2021, statewide vegetation clearing impacted less than one per cent of woody vegetation

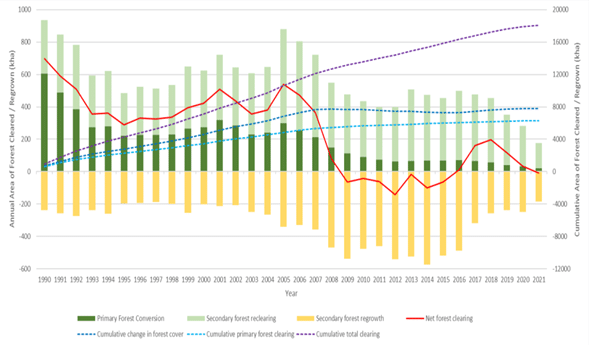

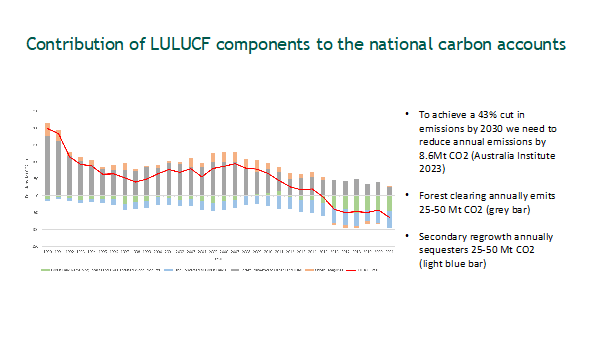

The next graph is more complex, but look at the red line, “net forestry clearing.” It is on a downward trajectory. These are NSW Government figures.

The contribution of primary (dark green bars) and secondary (light green bars) forest conversion, as well as secondary forest regrowth (yellow), to Australia’s annual net forest conversion area (red line).

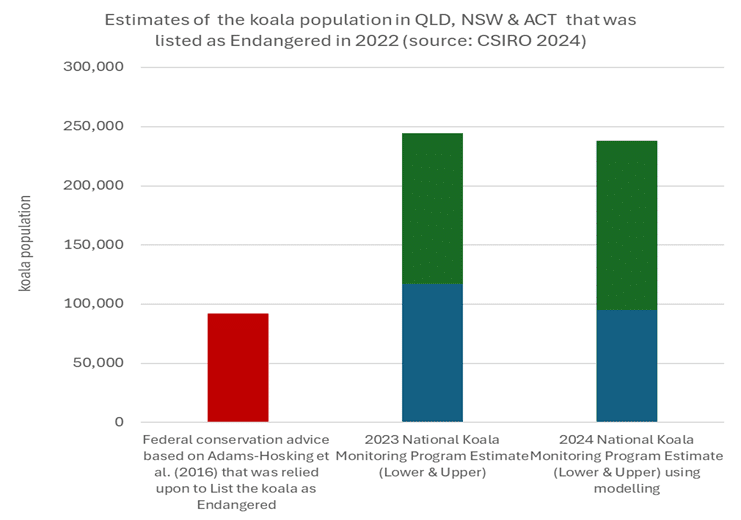

The argument mounted by organisation such as the WWF, Nature Conservation Society, Wilderness Society, National Parks Association is that native forest disturbance impacts koala populations. Indeed, these organisations and others pushed successfully to get the koala listed as an endangered species under the last Federal Coalition Government.

Native Forests and Carbon Sequestration

Environmentalists within the NSW Department of Environment and anti-Australian hardwood industry environmentalists are attempting to build desktop models that prove harvesting native forests for hardwood is a negative carbon sequestration exercise. This exercise has serious flaws that go unacknowledged. One is that the modelling basis contradicts the world’s best practice.

Another is fieldwork by the NSW Government on field data shows carbon sequestration is a strong positive. The Department of the Environment has consistently denied this research as it does not fit the “truth” they seek to develop.

The North East NSW Forestry Hub, in association with the North Queensland Forestry Hub, South & Central Queensland Forestry Hub, and the South East Forestry Hub, working with University of Queensland officers and an officer of the NSW Department of Primary Industry, is currently working on a project titled “Land Use, Land-use Change and Forestry.”

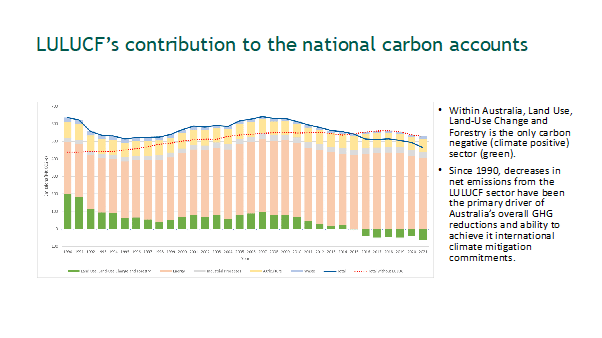

Some results are shown in the graphs below. Significantly, two findings are evident. Within Australia, Land Use, Land-Use Change and Forestry are the only carbon-negative (climate-positive) sectors. Forest clearing and forest regrowth produce a nil impact on carbon emissions, one balancing out the other. The findings also reveal forestry has better outcomes that lock up and leave.

Reserved land – National Parks and conserved areas.

Environmental groups seek to protect all productive or working forests in national parks with a ‘lock them up and leave’ management style. Venn observes that severe resource shortages have led to the adoption of a ‘benign neglect’ approach by default. He writes of Queensland, but the same can be said of NSW.

In 2023, the Department for the Environment requested five-year expenditure records for NSW National Parks and Wildlife under Freedom of Information. The data is not available; it has been disaggregated.

This benign neglect is impacting declining biodiversity outcomes. The last time data was analysed on biodiversity outcomes in a comparative manner between working State Forests and NSW National Parks was in 2013.

NSW State Forests came out well in front. The underlying issue is the amount of annual funding. This brings one back to the balance between land sharing and land sparing and the tension between ‘nature first’ and no human intervention. It is suspected that the disaggregation of NSW Data contributed to the 2013 data comparison results.

This work is considered below:

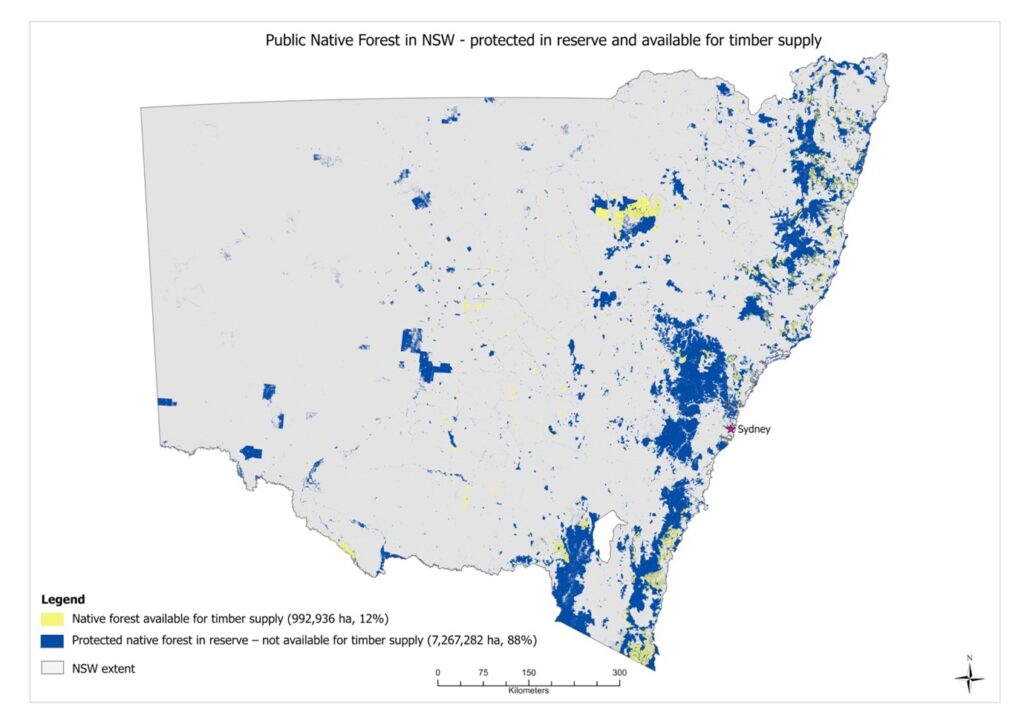

The following map highlights the location of areas of NSW State native forest (public land) that are available for native forestry operations (12%) and the area of public native forest that is inaccessible or locked up (88%). The NSW National Parks within the NSW Department for the Environment allegedly manage this native forest for biodiversity conservation in formal and informal reserves.

Biodiversity

The modelled extinction rate for fauna and flora is the underlying issue for much of the land-sparing support against a shared model of land sharing and land sparing. This uncompromising position is mirrored in Australian legislation from International Agreements, which Australia is a signatory.

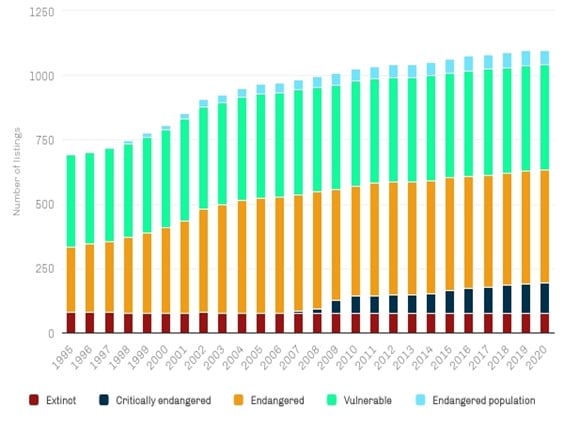

The graph below, taken from the NSW State of the Environment Report prepared by the NSW Government through the Environmental Protection Agency, shows the increasing trend of threatened biodiversity within the State. Environmentalists who attribute this matter to native forestry operations are alarmed.

Change in the Number of Listed Threatened Species in NSW

Change in the Size of NSW National Parks and Reserves

In NSW, 88% of public native forests are managed for biodiversity conservation in formal and informal reserves. This should be an alarm bell as the trend line for threats to biodiversity is on an upward trajectory.

This should be an alarm bell, yet that particular bell, if it is ringing, is very faint.

The bell that is not ringing is that as the size of the NSW National Parks and Reserves increases, so has the number of listed threatened species. It will be observed that there is a clear correlation between the last two graphs; both graphs rise together. The more locked up land, the greater the number of threatened species.

Only 12% of the public native forest’s estate is made available for long-term sustainable timber supply and other uses like apiary and recreation. On forested private land, the percentage is much lower (~6%). In any given year, less than 5,000 hectares of NSW native forest is subject to selective timber harvesting.

This represents one-quarter of one-tenth of one per cent (0.025%) of the NSW forest, equating to one tree in 4,000. The timber from this disturbance produces carbon-neutral fibre (timber) used in industrial and commercial settings.

International Biodiversity impacts

The Commonwealth enacted the Environment and Protection Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC) on 5 June 1992 following its international obligation as a signatory to the Convention of Biological Diversity. The Government ratified the Convention on 18 June 1993. The Keating ALP Government was the Commonwealth Government during these two years.

Where the Commonwealth legislates under the Australian Constitution’s external power, State Parliaments may also be bound to Commonwealth law. States have legislated for biodiversity measures, but as an administrative process, by agreement, they follow the EPBC Act’s Threatened Species Scientific Committee listings. This is so, even where the State might have set up its own Threatened Species Committee, such as NSW.

Understanding this material is important as it is the basis used by Australia’s environmental movement and bureaucrats to engage in a ‘land sparing’ approach. The counter approach, land sharing, is not openly advocated to challenge the “land spares.”

The 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) has three objectives:

- the conservation of biological diversity;

- the sustainable use of its components; and

- the fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising out of the use of genetic resources.

Key phrases in the CBD are:

“Sustainable use” means the use of components of biological diversity in a way and at a rate that does not lead to the long-term decline of biological diversity, thereby maintaining its potential to meet the needs and aspirations of present and future generations.”

This definition is no ‘land sparing’ orientated. It is suggested that it is “land sharing in meaning.”

“Biological diversity” means the variability among living organisms from all sources including, inter alia, terrestrial, marine, and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are part; this includes diversity within species, between species and of ecosystems.

“Ecosystem” means a dynamic complex of plant, animal and micro-organism communities and their non-living Environment interacting as a functional unit.

COP 15 was held in Montreal, Canada, and ended on 19 December 2022. The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) was adopted during COP 15, furthering CBD.

This historic Framework, which supports the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals and builds on the Convention’s previous Strategic Plans, sets out a pathway to reach the global vision of a world living in harmony with nature by 2050. Among the Framework’s key elements are 4 goals for 2050 and 23 targets for 2030.

The Official text of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework is known as decision 15/4. CBD/COP/DEC/15/4. Clause 2(f) references CBD/COP/DEC/15/13 which ‘recognises the critical role of actions for the restoration, conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity for helping address multiple global crises, including climate change and pollution, as well as biodiversity loss simultaneously.’

The Commonwealth Government on 14 March releases a discussion paper: Updating Australia’s Strategy for Nature. Australia’s Strategy for Nature 2019–2030 (the Strategy) sets a framework for action across all Australian governments and NGO sector to strengthen the national response to biodiversity decline.

The Strategy is being updated to reflect Australia’s contributions to the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (the GBF). The GBF is a once-in-a-decade international agreement that includes 23 targets to halt and reverse biodiversity loss by 2030 and 4 goals to live in harmony with nature by 2050.

Australia must update its strategy for nature and report back to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity in October this year.

Australia’s environment ministers agreed to develop national biodiversity targets for 6 priority areas. These are:

- Effective restoration of degraded terrestrial, inland water, marine and coastal ecosystems.

- Tackling the impact of invasive species.

- Building a circular economy and reducing the impact of plastics on nature.

- Minimising the impact of climate change on nature.

- Protect and conserve 30% of Australia’s land and 30% of Australia’s oceans by 2030.

- Work towards zero new extinctions.

Australia’s environment ministers also agreed that three enablers of change are required to support the delivery of the national priority areas and other GBF targets. These are:

- Ensuring environmental data and information is widely accessible and supports planning.

- Mainstreaming biodiversity considerations into government and business decision-making, including in financing, policies, regulations and planning processes.

- Ensuring equitable representation and participation in decisions relating to nature, particularly for First Nations peoples.

It will be noted that the ’30 by 30 campaign’ is included. Australian environmentalists take this to mean ‘lock up’ which results in benign neglect. Actions to support Conservation of Biological Diversity should not cause deterioration in natural habitats, impact future biological diversity or impede sustainable use.

The Hon Tania Plibersek MP, Minister for the Environment and Water, during her National Press Club speech on 19 July 2022, said:

“Our government will set a goal of protecting 30% of our land and 30% of our oceans by 2030,”

This follows the policy commitments by both the Coalition and Labor Governments to the global High Ambition Coalition for Nature and People, which has a global goal to protect 30% of land and seas by 2030.

The estimated value of loss of agriculture in NSW would be possibly between $5B and $8B.

The independently estimated value per annum to the NSW economy would be:

- $2.9B in gross revenue,

- $1.1 billion in gross Value Added, and

- 8.900 FTEs

The WWF has urged the Australian Government to set up a $5B Green Fund to acquire forests, productive land, and reforest wheat fields. The WWF-A released a Report on the issue.