As the world grapples with a timber shortage, the construction industry is turning to innovation to create circular value-added products to meet future demand.

Now, timber companies are treating softwood pine with agricultural waste crops to create timber products that replicate the durability of tropical hardwoods.

The product is used in decking and cladding, and there are hopes that the product can be used as a substitute for at-risk tropical hardwoods like Mynamar Teak, which is used extensively in European and North American boat-building markets.

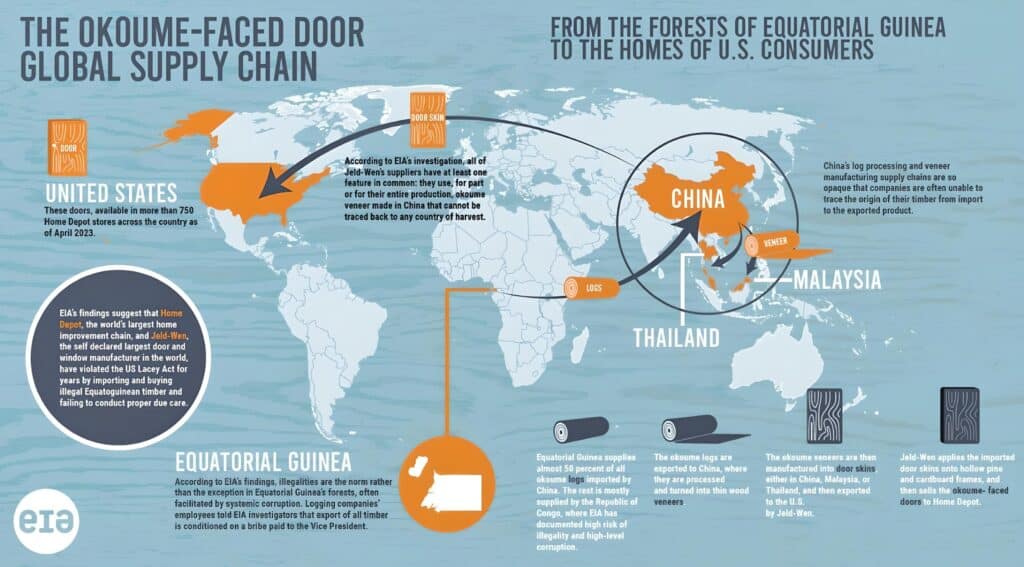

Not only could this reduce deforestation – with the EU introducing stricter rules around deforested products from next year – but it could also reduce the amount of conflict timber entering global supply chains.

In recent years, the EU has emerged as a significant market for tropical hardwoods, with data from Forest Industries Intelligence reporting that European hardwood imports reached their highest levels in over 15 years last year.

Yesterday, Wood Central revealed that the global supply chain for tropical hardwoods was “fertile ground for corruption,” with DW Europe reporting that “120 million tons of timber entering Europe had no official certificate of origin.”

The product uses NZ-based pine to create treated softwood timber emulating tropical hardwoods “without the environmental downsides.”

It takes softwood and treats it with a bio-based liquid, which permanently modifies the cell walls and gives it the characteristics of a hardwood, sourcing timber from faster-growing softwood plantations to meet the characteristics of tropical hardwoods.

According to Pavel Holub, Kebony’s Chief Technology Officer, the new product reduces deforestation – a byproduct of hardwoods imported from the Pacific via China – and can also meet the performance and aesthetics of tropical timbers.

“Wood from tropical rainforests is highly durable but ends with deforestation,” he said, before continuing that “fast-growing sustainable wood, mostly pine, can be transformed into something with similar performance and aesthetics of tropical wood.”

The company, founded in 1997, has a patent for kebonised wood, which “permanently changes the wood cells by furfuryl alcohol, produced from agricultural crop waste.”

The impregnation process lasts about a month, with Mr Holub telling the Financial Times, “What takes nature up to 200 years, it takes us 25-plus days.”

He concedes that the company took a long time to gain traction, with its first factory opening in Norway in 2009 and its second in Belgium in 2018.

The first, he said, runs on hydropower, whilst the second is powered by bio-mass from forest-based residues.

Now, the product is being sold in Germany, France, and the US, with plans to introduce the product into the Middle East “and anywhere where tougher regulations and restrictions around tropical hardwoods exist.”

According to Mr Holub, the main reason architects turn to tropical hardwoods is durability and minimal need for maintenance.

Nonetheless, he points out that standard wood for decking and terracing still requires repainting every two to three years.

“Architects are increasingly looking to use natural materials, with wooden buildings becoming more popular in many countries,” he said; however, the recent economic slowdown across Norway’s forest products industry has been brutal on the company.

According to Liesbeth Bracke, the company’s Chief Marketing Officer, Kebony’s sales have dropped for the first time in years amid a European-wide construction downturn.

“It has been a big hit, with a 30-40 per cent decrease in turnover,” she admits, with last year’s revenues (€ 58 million) a long way short of its €100 million by 2026 goal.

The company’s push into the Middle East will make it less sensitive to the construction cycle, with the company also looking to the US to produce manufactured products using southern yellow pine.

“Most types of wood can be kebonised, but some are better in terms of speed, durability and cost,” Mr Hulob said.

However, pricing is a growing challenge, with the dumping of tropical hardwoods into the US market by Chinese-based exporters making Kebony products uncompetitive.

“Our view is the price point should be similar,” Ms Bracke said, “I don’t want sustainable materials to be more expensive.”