US particle physicists now believe trees can operate as radio antennae for high-frequency space matter, with forests offering a far cheaper and more effective alternative to artificial antennae in picking up neutrinos in space.

The idea of using trees as radio antennas is not new, with the US Army wrapping extensive magnetic induction coils around trees to improve the audibility of radio signals in the jungle during the Vietnam War.

However, Professor Steven Prohira, from the University of Kansas, said forests can now be used to operate a global network of radio antennas, arguing that woody objects can operate similarly to highly sophisticated detectors, spotting Cherenkov radiation produced when neutrinos collide with ice or water.

Whilst Global scientists are looking at Giant Radio Array for Neutrino Detection (GRAND) antennas – which detect secondary particles created from collisions between high-energy neutrinos and particles in the atmosphere, Professor Prohira argues that the cost of logistics of operating 20 giant radio antennas, each covering more than 10,000 square kilometres is not sustainable.

“The big question with high-energy neutrino detectors is how to instrument a large enough volume actually to detect a measurable flux of neutrinos,” according to Professor Prohira, who hit upon the idea of using trees as radio antennae when thinking about how to construct a large-scale instrument using infrastructure that already exists.

He said the research to date showed that instrumented trees produced stronger and clearer signals than manufactured antennas. “The preliminary studies that I can find in the literature seemed quite promising,” Professor Prohira notes.

Although trees work across a wide range of radio frequencies, Professor Prohira thinks much more work will be needed to explore how they perform at frequencies of interest to tau neutrino detectors, which are higher than those generally used for radio communications.

The beauty of trees “is that they are already in place,” he said, “adding that uniform spacing of trees in the forest should make it feasible to create an array of tree antennas, which is very similar to the GRAND experiment currently proposed by European scientists.

“It is worth exploring because if it turns out to be relatively easy to instrument the trees and they work fairly well as antennas, that could open up the potential to being able to instrument a large-scale array in an efficient array,” according to Professor Prohira, who nonetheless warns that there may be “particular logistical challenges to a forest detector that make it unfeasible”.

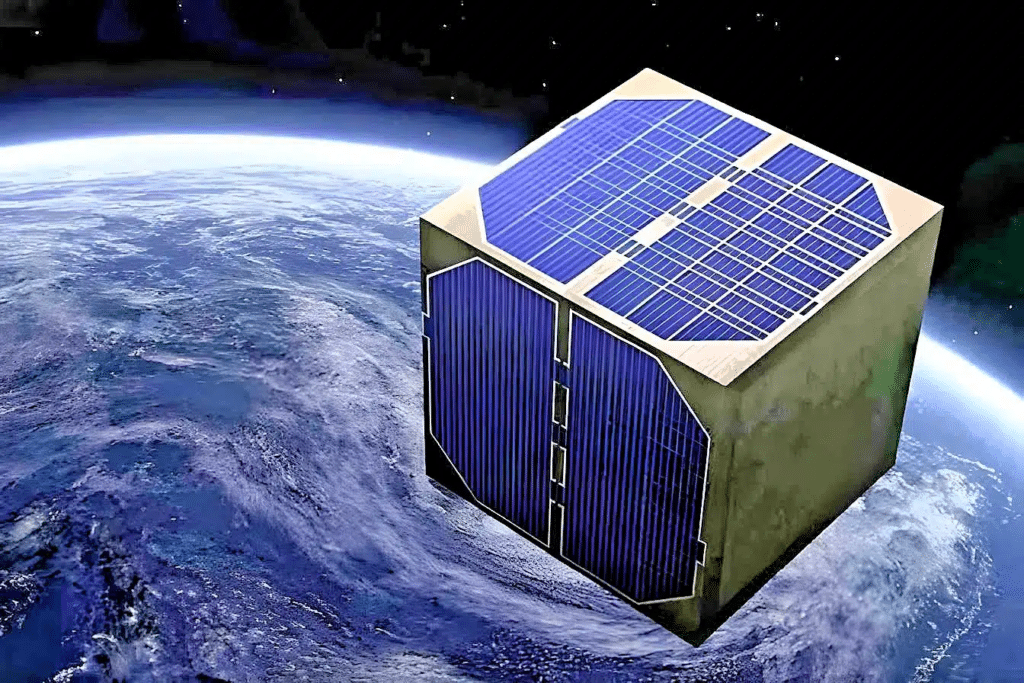

The push to use trees to monitor space frequency comes after NASA and Space X announced plans to launch a wooden satellite in space last week.

Known as the LignoSat probe, the satellite is the invention of Japanese scientists, who, combined with Japanese forest giant PEFC-certified Sumitomo Forestry, discovered that magnolia wood is the ideal alternative to earth-polluting metals used in satellites.

Already, the material has been tested at the International Space Station, with Wood Central reporting in May that an international team of scientists led by Kyoto University in Japan proved beyond doubt that exposed wood showed negligible deterioration and maintained stability in space.

The push to use biodegradable materials in satellites comes as the global space industry looks for cleaner, greener and more sustainable materials amid a purge of space waste that is now littering the earth.