Australia’s koala population – listed as “Endangered” in Queensland, New South Wales and the ACT since 2022 – is far larger than estimated, thanks to groundbreaking data released by the CSIRO.

Published as part of the CSIRO’s National Koala Monitoring Programme (NKMP), which has, since 2023, used expert data rather than expert opinion to calculate Koala abundance and disturbance.

And the results are surprising, with the CSIRO estimating the current population range between 287,830 and 628,010, about ten times more than the numbers forecast by the Australian Koala Foundation (between 32,000 and 58,000 in 2021 after the Australian Black Summer bushfires).

In effect, Koala numbers are now higher than in 2012 (forecast to be 144,000 to 605,000), when Koala populations were classified as “vulnerable” and not “endangered.”

Whilst solely data-driven estimates have challenges—namely limited and fragmented data—the CSIRO states that they “have two distinct advances” over past estimates: “The first of these was a concerted effort to collate koala presence, absence, and abundance data from a wide range of sources (individuals, research organisations, community groups, local governments, and state governments). The second “is an analytical framework combining all these disparate sources and data types.”

Fact Check: Huge Study Finds Koalas Not Endangered in NSW Park!

CSIRO’s data comes after Wood Central revealed that koala populations are “high and stable” in NSW forests, with large populations thriving in public forests that are not influenced by timber harvesting.

That is according to new research published by Dr Brad Law, the principal research scientist at the NSW Department of Primary Industries, and supported by Leroy Gonsalves, Traecey Brassil and Isobel Kerr.

Published in April, Broad-scale acoustic monitoring of koala populations suggests metapopulation stability, but varying bellow rate, in the face of major disturbances and climate extremes, has, for the first time, used passive acoustic monitoring to analyse populations in state forests now earmarked for the Great Koala National Park.

According to Dr Law’s research, “regulated timber harvesting in state forests did not affect the trend of (koalas) either metric nor did land tenure,” with state forests (where timber harvesting is permitted) or national parks having little impact on the population of koalas.

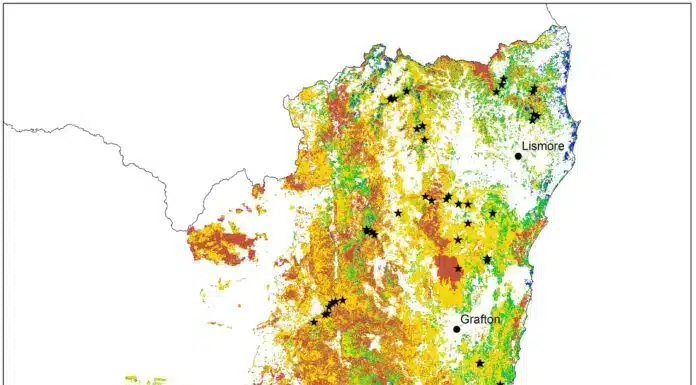

The findings come after a 7-year study between 2015 and 2021, covering more than 224 sites spread across more than 8.5 million hectares of forest area. Capturing the 2019/20 Black Summer Fires, the study reports that whilst Koalas are cryptic, “acoustic sampling over many thousands of hours, combined with semi-automated call recognition, has proved exceptionally effective at detecting the species,” with high precision.

“Occupancy was high over an extensive area of habitat,” the research said, with “the stable trend maintained despite a severe drought that led to mega-fires burning about 30% of their habitat in 2019.”

Scientists use GPS and LiDAR satellites to monitor impacts in Koala coups

The new research comes after Dr Law’s published, GPS tracking reveals koalas Phascolarctos cinereus use mosaics of different forest ages after environmentally regulated timber harvesting earlier this year, which used GPS-tracking and remote sensing, including LiDAR satellites, to create timber mosaics to evaluate the impact of harvesting on Koala coups.

Working with Forestry Corp and the Port Macquarie Koala Hospital, Dr Law said GPS tracking, combined with remote sensing, “provides a high-resolution picture of how individual koalas use the forest 5-10 years after timber harvesting.”

“These results strongly support our acoustic surveys (previously published) demonstrating high occupancy (of Koalas) in northeast NSW and no difference in density between harvested forest in the state forest and controlled forest in the national park,” Dr Law said, adding that it also offers insights into how koalas use areas that are heavily managed or where regeneration and restoration is a significant part of the landscape.

- To learn more about the National Koala Monitoring Programme and current 2024 population levels, visit the CSIRO website.