New research from the University of Maryland reports that an area of tropical forest the size of Switzerland was lost last year as tree losses surged.

It means that a political commitment to end deforestation made at COP26 by world leaders is well off track.

According to the university’s Forest Pulse, 11 football pitches of forest were lost every minute in 2022.

Brazil was responsible for 43% of the world’s total loss of forest area, equivalent to 1.78 million hectares of primary loss.

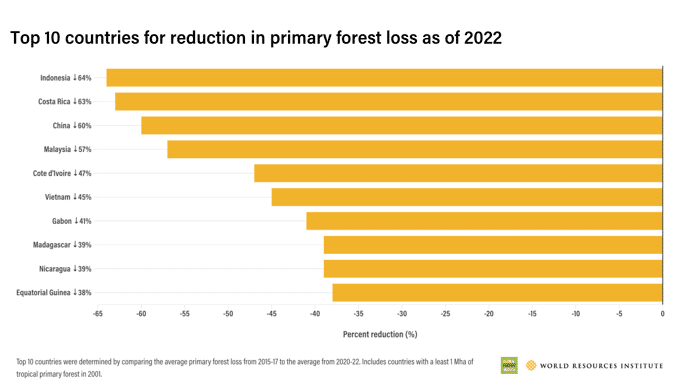

But a sharp reduction in forest loss in Indonesia and Malaysia, both at near record lows, shows that reversing this trend is achievable.

COP26 pledge to halt and reverse forest loss has not been met

One of the critical moments at the COP26 climate meeting saw over 100 world leaders sign the Glasgow Declaration on forests, where they committed to collectively work to “halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030”.

Leaders from countries covering around 85% of global forests signed up

Commitments included former Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro, who had relaxed enforcing environmental laws to allow development in the Amazon rainforest.

Earlier this month, Wood Central covered Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Deforestation in the Amazon, which aims to strengthen the country’s commitment to the Glasgow declaration.

“Brazil has resumed its leading role in tackling climate change after four years in which the environment was treated as an obstacle to the immediate profit of a privileged minority,” Lula said in a post on Twitter, alluding to the policies of his predecessor, Jair Bolsonaro.

However, Brazil has a long way to go to correct surging deforestation rates.

In March 2022, Mongabay monitored Brazil’s performance against its global commitments to restore tens of millions of hectares of forest.

It found several major bottlenecks for restoration, including greater transparency and standardisation in reporting, delays in reforestation and restoration projects and Brazil’s forest laws.

Rainforests act as global carbon sinks

Rainforests in Brazil, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Indonesia absorb huge amounts of greenhouse gases.

Clearing or burning these older forests sees that stored carbon released into the atmosphere, driving up temperatures worldwide.

These forests are also critical for maintaining biodiversity and the livelihoods of millions of people.

Scientists warn that these functions – or “ecosystem services” – can’t easily be replaced by planting trees elsewhere because these forests have developed for a long time.

According to the new data, the tropics lost 10% more primary rainforest in 2022 than in 2021, with just over 4 million hectares lost in felling or burnt trees.

This resulted in releasing carbon dioxide equivalent to India’s annual fossil fuel emissions.

“The question is, are we on track to halt deforestation by 2030? And the short answer is a simple no,” said Rod Taylor from the World Resources Institute (WRI), which runs the Global Forest Watch.

“Globally, we are far off track and trending in the wrong direction. Our analysis shows that global deforestation in 2022 was over 1 million hectares above the level needed to be on track to zero deforestation by 2030.”

Brazil dominates the losses of primary tropical forests; in 2022, this increased by over 14%.

In Amazonas state, which is home to over half of Brazil’s intact forests, the rate of deforestation has almost doubled over the past three years.

Signs of improvement in Indonesia and Malaysia

While the overall picture is not good, some positive developments show that it is possible to rein in deforestation.

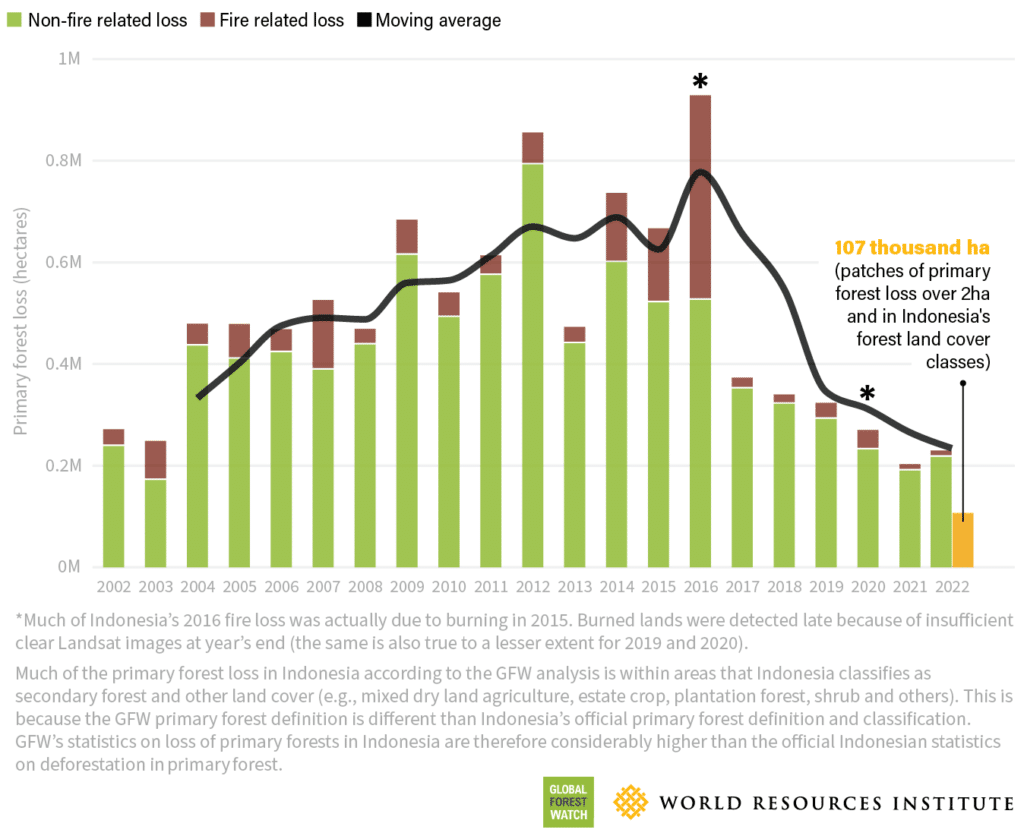

Indonesia has reduced its primary tropical forest loss more than any other country in recent years since recording an all-time high in 2016.

Analysis suggests this is down to both government and corporate actions.

A moratorium on logging in new palm oil plantations was made permanent in 2019, while efforts to monitor and limit fires have been reinforced.

It’s a similar story in Malaysia.

In both countries, oil palm corporations are acting, with some 83% of palm oil refining capacity now operating under no deforestation, no peatland and no exploitation commitments.

In Sarawak, Malaysia’s largest state, forests cover 91% of its land area – or about 9.57 million hectares of forest area.

In 2022 it lost 59,000 hectares of natural forests, a drop of almost 300% from a decade ago.

Earlier this week, Wood Central covered the Malaysian Timber Council’s master plan to invest in plantations using indigenous seedlings as part of their commitment to no deforestation commitments.

The main drivers of deforestation is cocoa farming and palm oil

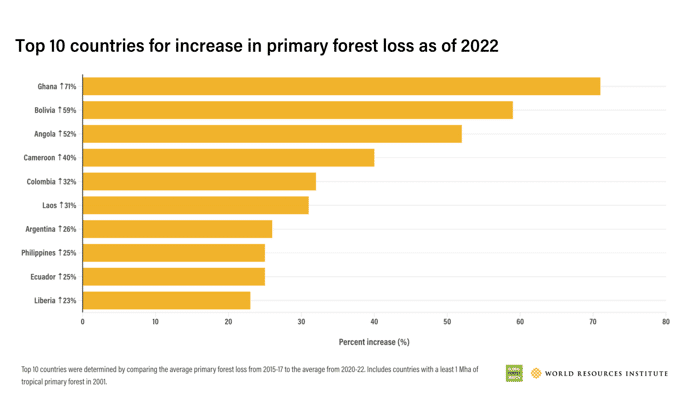

Commodity agriculture, palm oil and even the thriving balsa wood industry – as reported by Wood Central yesterday – are among the drivers of deforestation in the top 10 countries.

In Bolivia, one of the few countries not to sign the Glasgow Declaration, the country experienced a rapid acceleration of forest losses in 2022, up almost a third in a year.

Commodity agriculture is the primary driver, according to researchers. Since the turn of the century, soybean expansion has resulted in nearly a million hectares of deforestation in Bolivia.

Although Ghana in West Africa has only a small amount of primary forest remaining, it saw a massive 71% increase in losses in 2022, mostly in protected areas.

Some of these losses are close to existing cocoa farms.

According to Rod Taylor, the time for action on deforestation is now.

If the world wants to keep global temperatures under the critical 1.5C threshold, the time for action on forests is now.

“There’s an urgency to get a peak and decline in deforestation, even more urgent than the peak and decline in carbon emissions,” said Rod Taylor.

“Because once you lose forests, they’re much harder to recover. They’re kind of irrecoverable assets.”

In May 2023, the EU introduced a landmark regulation which makes companies responsible for ensuring their products do not contribute to deforestation.

Under the EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR), the Europeans have banned the sale of coffee, cocoa, cattle, palm oil, soy and wood connected to deforestation.

Wood Central has previously covered the law and how it works.

!["This is a very strong result. We don't want to be complicit anymore in this global deforestation happening a little bit in Europe but first and foremost in other parts of the world," said the lead negotiator for the European Parliament, Christophe Hansen from the European People’s Party after the vote. [Copyright: © European Union 2023 - Source : EP]](https://woodcentral.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Hansen-1024x576-1.jpg)

How is deforestation measured?

The tree cover loss is analysed via satellite images – although there’s sometimes uncertainty about the precise year trees are lost.

Measuring deforestation – which typically refers to human-caused, permanent removal of natural forest cover – is more complicated because not all tree-cover loss counts as deforestation.

Scientists try to consider all of these factors to come up with an estimate for deforestation.

The latest figures suggest a rise in (human-caused) global deforestation of about 3.6% in 2022 compared with 2021 – the opposite direction to the Glasgow commitments.

The BBC reports that whilst losses of the critical primary tropical forests rose by nearly 10% in 2022, overall global tree cover loss from all causes fell by almost 10%.

But researchers say this was because losses from forest fires were down in 2022, particularly in Russia.