The latest monumental UN Climate Change report dwells much more on what to stop digging up and burning, than on what we should do about retaining all the benefits of forests. However, it serves as a wake-up call to alert us to what we can all do to change things for the better.

As it’s the International Day of Forests – March 21 – on the same day that the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report is released, I cannot help but use the occasions to reflect on what I know of our forests and what I’ve been devoting a lot of attention to over the past few years.

For a start, I must add some additional warning signs.

Unrelated to the “new” climate report, was this headline which greeted me just two days ago: “Mountain forests disappearing at alarming rate: study”.

The AFP report from Washington, which also ran in Singapore’s Straits Times, announced: “Logging, wildfires, and farming are causing mountain forests, habitat to 85% of the world’s birds, mammals and amphibians, to vanish at an alarming rate”.

The study was published in the journal One Earth and was the work of a team of scientists led by Xinyue He, Dominick Spracklen and Joseph Holden at Leeds University in the United Kingdom, and Zhenzhong Zeng at the Southern University of Science and Technology in China.

They told us that globally, we have lost 78.1 million hectares (7.1%) of mountain forest between 2000 and 2018—an area larger than the size of Texas. Much of the loss occurred in tropical biodiversity hotspots, putting increasing pressure on threatened species.

We are also reminded that “though their rugged location once protected mountain forests from deforestation, they have been increasingly exploited since the turn of the 21st century as lowland areas become depleted or subject to protection”.

Sadly, the report goes on to say that “logging was the biggest driver of mountain forest loss overall (42%), followed by wildfires (29%), shifting or “slash-and-burn” cultivation (15%), and permanent or semi-permanent agriculture (10%), though the importance of these different factors varied from region to region.

Where is this happening, you might well ask? The researchers point out that “significant loss occurred in Asia, South America, Africa, Europe, and Australia, but not in North America and Oceania”.

You need to drill down in the report for more details on Australia’s state of affairs, and it does identify two studies around the impact of the 2013 “Red October” bushfires in New South Wales.

Interesting the report doesn’t go into more recent events than that, so doesn’t include the devastation and forest loss caused by the Australia summer fire season of 2019/20.

But we shouldn’t be too smug about it, as our near neighbours in Asia, including Indonesia, figure prominently in this and other reports.

If we turn to another solid piece of research – Deforestation in Southeast Asia: Causes and Solutions in Earth.org – we learn:

“Southeast Asia, including Indonesia, Malaysia, Vietnam, and Thailand, is home to nearly 15% of the world’s tropical forests, which makes it all the more attractive as a deforestation hotspot. The region has one of the highest rates of deforestation, losing at least 1.2% of its forests annually, which is comparable only to Latin America where deforestation rates in the Amazon account for one-third of global tropical deforestation.”

Deforestation in Indonesia is particularly rampant, the Earth.org report shows, compared to its Southeast Asian neighbours. Figures from 2019 show that Indonesia alone was responsible for nearly 14% of global tropical deforestation.

Of course, we know that Indonesia and other Southeast Asia countries insist that that they’re getting deforestation under control.

Then we read that the biggest contributor to deforestation in this region is palm oil production, with logging activities hot on its heels. This includes wood, paper and pulp, as well as timber plantations, which have been persistent contributors to deforestation in Southeast Asia, with the biggest danger stemming from illegal logging.

Land conversion into croplands and pastures still remains one of the drivers of deforestation in the region, disadvantaging smallholder farmers, who own an average of just 2.5 hectares of land in Indonesia. They compete with large and organised plantations, prioritising “profitability over environmental stewardship” in the process, Earth.org reminds us.

Back to today’s UN climate change update, which tells us – among many other important things – that the solution lies in climate resilient development.

This involves integrating measures to adapt to climate change with actions to reduce or avoid greenhouse gas emissions in ways that provide wider benefits.

To me that includes forest conservation, reforestation, restoration and zero deforestation.

“Mainstreaming effective and equitable climate action will not only reduce losses and damages for nature and people, it will also provide wider benefits,” said IPCC Chair Hoesung Lee.

This Synthesis Report underscores the urgency of taking more ambitious action and shows that, if we act now, we can still secure a liveable sustainable future for all.

Another of the report’s authors, Christopher Trisos, had this to say:

“The greatest gains in wellbeing could come from prioritizing climate risk reduction for low-income and marginalised communities, including people living in informal settlements.

“Accelerated climate action will only come about if there is a many-fold increase in finance. Insufficient and misaligned finance is holding back progress.”

If we can, collectively, improve access to clean energy and technologies, at the same time we significantly improve health, especially for women and children. Then there’s low-carbon electrification, walking, cycling and public transport enhance air quality, improve health, employment opportunities and deliver equity.

The report points out, quite significantly I think, that “the economic benefits for people’s health from air quality improvements alone would be roughly the same, or possibly even larger than the costs of reducing or avoiding emissions”.

Improving the urban environment with more trees – and leaving more intact while development goes on around the green space – would be a great help in Australia and in cities the world over.

While trees mean livelihood for many people, if we can manage our forests in a sustainable and responsible fashion, we can get all the benefits they provide. For the health of all of us – people and the environment. The very air we breathe.

Which reminds me of what I wrote last year about the work of a company called Greehill in Singapore.

My article in Asian Journeys, posed a few questions and came up with some answers:

How do you put a price on a tree? Or to ask the question in more convoluted terms: How can “monetary valuation function” quantify the social, ecological, and economic benefits of trees?

Of course, if you’re buying a plant from a nursery, which you sincerely hope will grow into a tree to provide shade and shelter in your garden, you know exactly what it’s going to cost you.

Then you must take into account the cost of caring for that tree, with water, mulch, and anything else needed to sustain its growth.

But what about all the existing trees in your street and neighbourhood? In your city. Country wide. Even further afield. How to assess the value of trees? The benefits they provide to us all? For our health and the health of the planet?

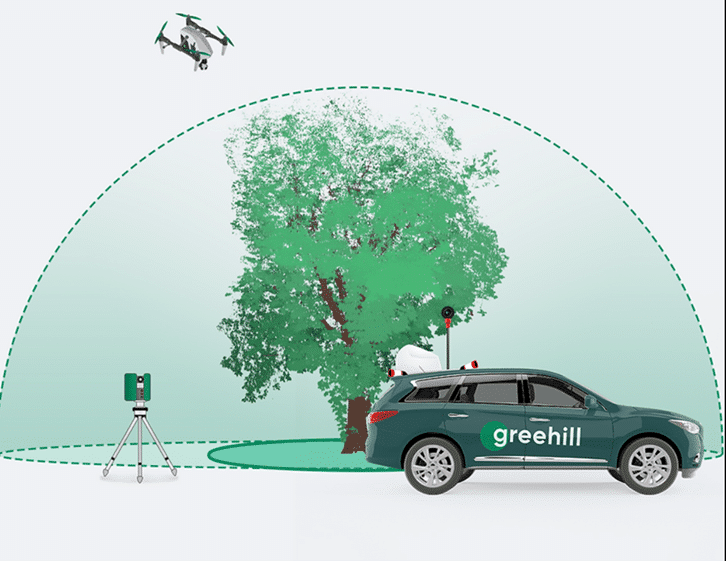

When we met at the World Cities Summit in August 2022, Mr Gabor Goertz, CEO and co-Founder of Greehill, told me that his company has “powered digital urban forest management” since 2017 for the National Parks Board of Singapore (NParks).

This sensitive equipment collects data from every tree which comes into its sights. It produces a computerised 3D model – which Greehill calls “a digital tree” – so his team can perform health and safety checks, undertake custom measurements, as well as filter trees based on other important criteria. His data collection process can track 50,000 trees a day.

All this is essential to gather and retain climate and ecologically relevant data, including the amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) stored by each tree. Or even how a park with lots of trees can cool the adjacent area.

Appreciating the trees around us for all they’re worth. That’s the ultimate answer.

On International Day of the Forest and the day the UN presents its major report, which has been ten years in the making, we can remind ourselves of the true value of every tree on the planet.