In most of the discussion concerning the judgement of Federal Court Justice Perry last Wednesday, much of the commentary has suggested that the industry would close or collapse without the Regional Forestry Agreement (or RFA).

However, this is entirely incorrect!

An RFA is simply an agreement between the Commonwealth and the state to regulate forestry operations at the state level, thus giving the state regulatory bodies control over compliance.

There are plenty of other examples where the Commonwealth devolves power to the state.

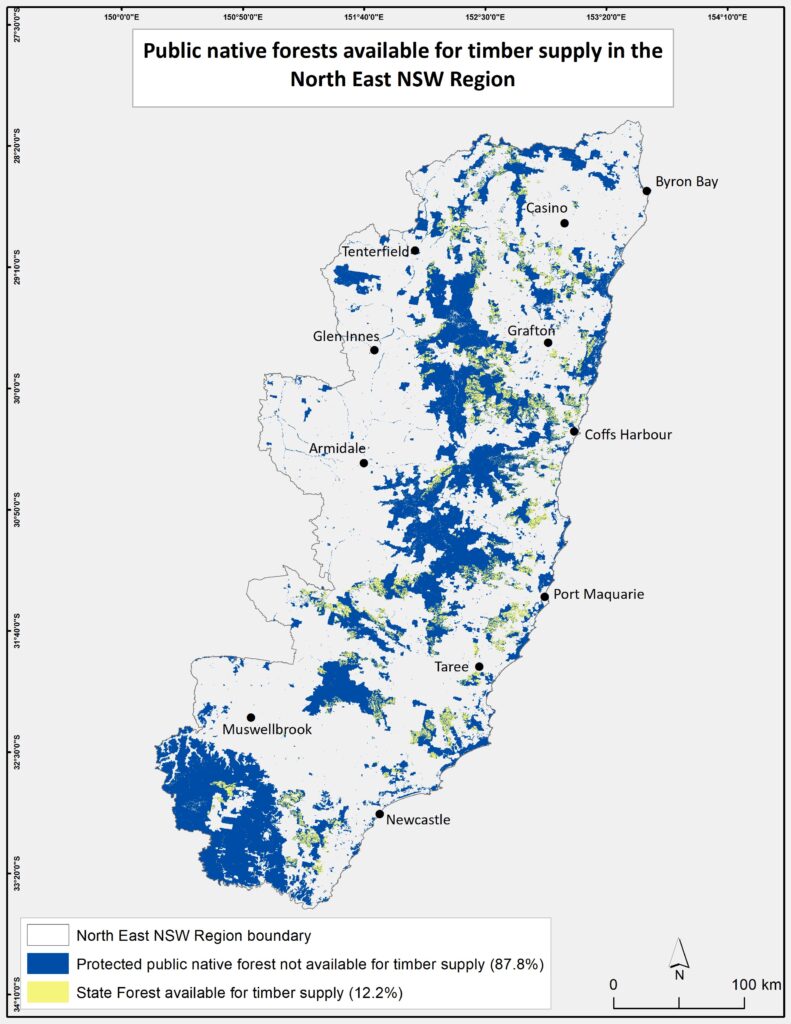

In NSW, after 2000, when the NE NSW RFA was signed, the industry was controlled by the various State pieces of legislation designed to protect biodiversity and provide an industry.

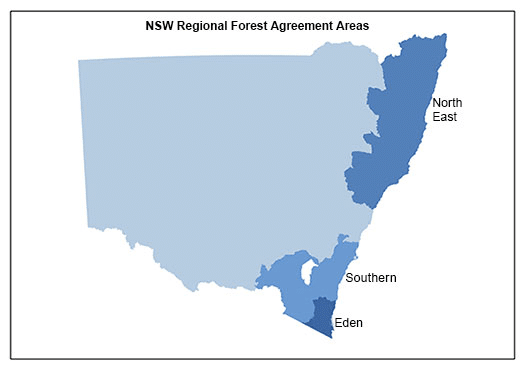

Essentially, the coastal forests of NSW have an RFA; however, in the western division of NSW, where red gum, cypress and western hardwood operations occur, there is no RFA.

Similarly, there is no RFA operating in Queensland. It does not mean that if there is no RFA, there is no protection for forests, fauna, and flora.

In NSW, the industry, whether in an RFA region or not, is controlled by the Protection of the Environment Act, the Forestry Act, the Local Land Service Act (LLS), the Biodiversity Act, and all other NSW State legislation.

Within those, there are what are called Integrated Forest Operations Approvals (IFOA) for each region.

They require stringent planning and assessment processes for state forests and assessments for private land through LLS. Detailed fauna and flora surveys are conducted on state forests and submitted to the EPA with a harvesting plan.

So, this court case was simply a judicial review of the renewal process.

There was no need to go through the same process that occurred between 1992 and 2000 because the reporting to both state and federal bodies is extensive as part of the IFOA process. There is a review of the RFA every five years. Everything is reported and transparent.

Put simply, this court case was a judicial review of the process used to renew the NE RFA. Not hearing evidence about operations, threatened species, floods or fires. There was a contention that climate change had not been considered, but it is in the renewal document.

Had the case brought by NEFA/EDO been upheld, it would simply invalidate the NE NSW RFA only and require any exported wood to have special export licences (which they have, anyway).

There is not enough hardwood domestically to supply the domestic market, so other than softwood, almost nothing goes out of NSW for export – used in flooring, decking, cladding, windows, structural parts of buildings, joinery, kitchens, power poles, pallets, railway sleepers, fencing, piers, bridges and many more applications.

An adverse decision does not mean that forest operations are illegal or that there is no regulation and compliance. The state legislation and regulations keep applying.

Had the finding been adverse and the NE RFA deemed invalid, there would have been no requirement for the Federal or State to do anything, and the industry could have kept operating the same way under strict state controls.

Suppose a government wishes to close down hardwood forestry. In that case, it is a political decision, not a legal decision and will involve restructuring businesses, paying out employees, etc.

It costs tens of millions of dollars – more money than allowing the industry to keep operating, keep people in rural, regional areas employed and products in the supply chain.

WA and Victoria now realise the allocated payouts are only the initial part of the cost, with both governments now paying high prices for imported timber for their government projects alone.