Do you know where your timber comes from? That is the question posed by Madeleine Osborn, the acting director for Australia’s Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry after new data revealed that shipments of Russian veneer and Burmese teak continue to arrive at Australian ports every month.

Ms Osborn, who, under new laws, can test imported timber to check species and the country of origin, said: “15% and 30% of all timber traded (globally) is potentially illegal, including 10% in the Australian market.”

And that number is expected to rise sharply as Australia increasingly relies on imported hardwoods—used in floors, decks, furniture, notepads, toilet paper, tissues, and prefabricated buildings—in the wake of the Victorian and West Australian decisions to exit from native forestry.

It comes after Wood Central revealed that up to 25% of all timber tested as part of a new DNA trial was flagged as illegal, making Australia a hot spot for the world’s most profitable transborder environmental crime.

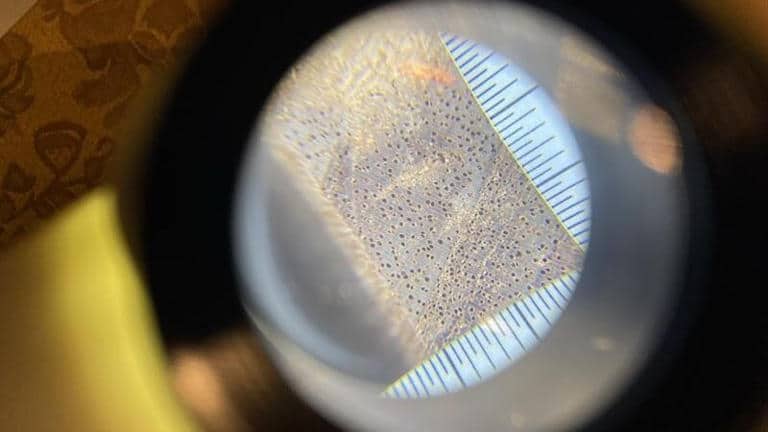

“We chose [technologies] that have fairly robust reference databases,” Ms Osborn said. “You can compare that to a fingerprint database that the police use. You must have something to match your results against, so building those reference databases is a real priority.”

According to Ms Osborn, about 25 per cent of products tested had inaccurate species and origin claims: “It wasn’t a random test, so we can’t say that that’s the complete representation of what’s happening on the market.”

“But it certainly suggests that there’s room for improvement,” she said.

“The information that [importers] are being provided by their overseas suppliers is potentially misleading.”

Madeleine Osborn, the acting director for Australia’s Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry

Wood Central understands that the trial, which involved 140 products and 39 distinct species, found multiple instances of undeclared veneers and solid timber products with potential Russian origins. It also found a significant amount of undeclared content in paper products, confusion around Burmese teak, as well as oak coming from Europe and the US.

Call for new timber labelling laws.

According to Diana Hallam, the CEO of the Australian Forest Products Association—the country’s peak industry group for forest products—testing for illegal timber has presented considerable challenges.

“We import timber products that are effectively 25 layers of timber compressed very tightly together, and testing has not been possible without some of the new technologies,” Ms Hallam said.

However, Ms Hallam was surprised by the scale of the trial’s findings.

“I didn’t think it would be as high as one in four,” she said. “That has increased our interest in speaking with the government about country-of-origin labelling laws for timber and timber products.

“We want a very strong compliance and enforcement regime and country of origin labelling so that Australians can go into their local … hardware store, select some timber, and have confidence in where it has come from.”

Ms Hallam said it should be easier for customers to buy Australian-grown timber. “I was involved in reforming the country-of-origin labelling food laws, and I know consumers want that information,” she said.

“I would like to see more support from the government into implementing a regime similar to that we have in food,” she said. “You should be very clear about whether it’s Australian and where it’s sourced.”

- To learn more about the challenge faced at Australian Ports, click here for “Crackdown: How Australia Tackles Illegal Timber at Ports.“