Changing the carbon methodology to incentivise the removal of managed forest harvesting could lock the Australian economy out millions of tons of carbon additionality.

In an exclusive interview with Wood Central, a director of Margules Groome Consulting, Damien Walsh, said, “the science is there” to support sustainable harvesting of managed native forests.

“But, to reach this conclusion, you need to consider the carbon storage in wood products produced, the replacement of fossil fuels with forest biomass for energy generation, and the substitution of more carbon emission-intensive construction materials with wood products.”

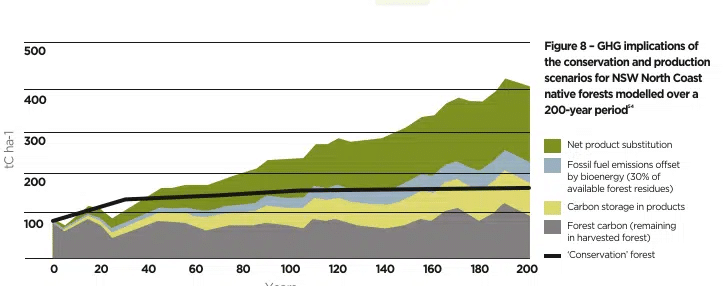

He points to a recent Forest and Wood Products Australia report, which claims that the carbon stored in a harvested forest on the NSW North Coast, the site of the Great Koala Park, is greater over time than a forest managed for conservation.

“Obviously, every forest is different, and there are numerous variables that need to be taken into account,” he said, “but the key is that conservation forests eventually reach a stage where the growth slows where carbon from growth equals the emissions from decay and decomposition.”

When this happens, forests become a fixed carbon store and no longer can provide additionalality back into the market.

He said harvesting ensures that forests “always grow or regenerate,” with constant carbon sequestration occurring at a level “greater than emissions from decay and decomposition when you look at the whole life cycle analysis of a timber supply chain.”

It comes as the right-leaning Blueprint Insitute has released successive reports in Victoria, NSW and most recently, Tasmania, suggesting that ending native forest harvesting could save millions of dollars.

The institute is now pushing for the Australian Government to introduce a “robust carbon methodology” that allows the state to generate carbon credits by stopping logging and introducing conservation measures.

Last month, NSW Premier Chris Minns echoed the sentiment, suggesting the NSW Government is open to converting native forests into national parks but only if the Australian Government introduces a new emissions trading scheme “applicable for the NSW economy.”

Premier Minns claimed that with the UN introducing a new international carbon market, “many industries, companies and governments are desperate for carbon offsets and would be looking at jurisdictions like NSW.”

However, Mr Walsh suggests that a forest “look up” will ultimately result in the economy missing out on the carbon credits along the value chain. “If you look at the forest only, you see a carbon deficit caused by harvesting,” he said.

“I assume any native forest credit will be about crediting the different from the harvesting process, but you lose any ability to earn credits from green construction or fossil fuel replacement later in the supply chain.”

Then, there is the protection and storage of carbon stock.

“Governments are poor at resourcing national parks, and there is the fire risk,” Mr Walsh said, “what happens to the conservation forest if a major fire occurs?”

“Fires are generally worse in national parks because infrastructure has been closed or neglected, not enough preventative works like hazard reduction burns occur because they are left unmanaged.”

He said repeated catastrophic fire events would not only ruin any carbon storage but “may completely change forests’ dominant species, structure, and habitat value, so it will never regain that carbon storage, let alone the other values.”