Whilst sister resort Nikoi, a half-hour speedboat ride away, is made of driftwood, Cempedak is built entirely of sustainable bamboo, recycled teak and rubber wood and topped with grass-thatched roofs. There are literally no walls, not even in the second-floor bedroom and shower – the better to catch the sea breezes and be lulled to sleep by the softly lapping sea.” (From the original article in Wallpaper in August 2018, when Cempedak was selected as one of 10 hotels in the world its editors listed as having them “longing for island life”.)

I reported a month ago on what Andrew Dixon and investor friends have created on two relatively remote Indonesian islands, based on meeting and interviewing the man himself. On video as well:

But that was before I’d been there to see for myself…

Here, I focus on what I call a true ‘bamboo masterpiece’ on Cempedak Island. The concept, design, construction, and the first-hand experience of touching, feeling, and being inside these amazing structures made from the fast-growing sustainable tropical “grass,” which performs as well as wood and steel as a building material.

The Bamboo Breathes

Yes, I discovered that bamboo breathes! Once inside my Cempedak villa, I quickly accepted that bamboo is the most natural material to use in the structure, walls, panels, flooring, and even some of the furniture. You’ll find recycled teak in places and rubber wood on the outside deck.

As I report on this ‘visitor experience,’ I cannot help but describe it as a breath of fresh air, literally and figuratively. As you admire, see and smell the unique characteristics of the world’s most sustainable building material, you can also take in the cooling sea breezes, as there are few obvious walls and doors here to stop its flow.

Does it worry you there’s no air conditioning? The instant you arrive at your very open-to-the-elements villa you realise how the natural air flow – and the impressive ceiling fans – provides more than enough cooling.

Architect Specialised in Hotel Design

Back in 2013, Andrew Dixon and fellow Cempedak owners/developers retained Miles Humphreys, the New Zealand architect based in Bali, who specialised in designing hotels. He might not have had any direct experience working with bamboo at that stage, but he had some great contacts, including two young designers who he hired as they had worked exclusively with the sustainable building material. Together, they worked on the masterplan for the site and the conceptual drawings.

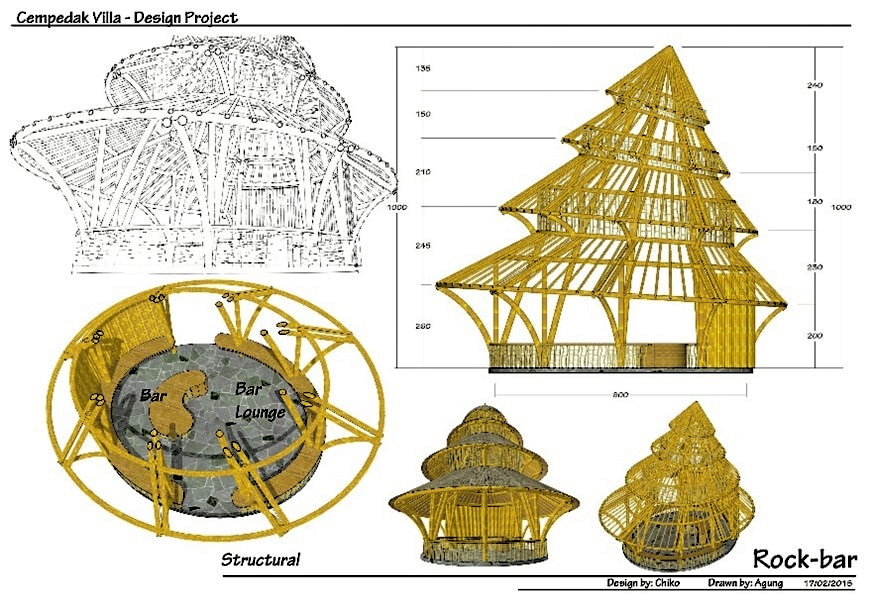

Miles, with his young Balinese architects, Chiko Wirahadi and Ketut Indra Saputra, then converted the conceptual drawings into ‘makets’ – bamboo models that were used onsite to build the structures.

Here is how a ‘maket’ is made:

Andrew Dixon explains: “Usually, we would go through a few iterations of these until we agreed on a final version. Using that model—there are no paper floor plans on site—the team then built a full-scale’ mock-up’. After building this, we made a few variations, which then became the version that we used for building all 20 villas.”

Collaborative teamwork

Miles, the architect and Andrew, the resort developer, called in a structural engineer who specialised in bamboo structures. While it all seemed quite complicated at first, it worked surprisingly well and became an excellent example of collaborative team-work.

Andrew is quick to draw to attention to the dedication and direction of the architectural team, led by Miles, who was particularly helpful to work with. He also praised the Balinese architect called Chiko, who worked on a few other structures, but most notably the very distinctive Dodo Bar. Built from black bamboo and black ijuk (arenga pinnata) palm fibre, it resembles a witches’ hat.

The architectural team introduced the Cempedak owners to a number of key contacts who played critical roles in getting the bamboo structures built, Andrew tells me, with one of the most important being Pak Indra, who led the construction team. He brought in a wealth of knowledge of bamboo and bamboo construction techniques.

Also around this time, an energetic English carpenter, Piers Berry, joined the team as Project Manager.

Not all Plain Sailing

In early 2015, building began in earnest with delivery by barge of the first major delivery of bamboo. It was not all plain sailing, though, Andrew recounts:

This barge got lost en route from Java due to bad weather (and maybe some poor navigation) and it was only with the help of the navy that it was located. Without it, the whole project would have been delayed at least six months as the bamboo is only harvested twice year.

By early 2017, 11 villas had been completed together with the restaurant, boathouse and bar. At the peak of construction, around 200 people were employed on site. In March 2017, Cempedak Island resort opened to its first guests.

We are reminded by Andrew and his astute staff, who happily take guests on what they call as ‘a bamboo building tour’, that there are around 1000 different species of bamboo. In building Cempedak, 10 different species of bamboo were used.

Aja – acting as the golf buggy driver – transported us everywhere on the island, even showing us the resort’s very own bamboo garden to see ‘how the various grasses grow’. He also took us to us the very well-equipped carpentry store, alongside a stack of massively tall and sturdy bamboo beams, ready if needed for replacement or support for any of the resort structures.

We learn that the strongest and most plentiful bamboo suitable for construction grows – and was sourced for this project – from nearby Sumatra, where you’ll find 75 species, 34 of which are endemic to the province.

No one farms bamboo in Sumatra on the scale that was required. Andrew explains: “We needed to establish a supply chain from selection through to transport and treatment of the bamboo. This was a huge logistical challenge”.

The primary species of bamboo used for the uprights is locally known as Petung. These large structural uprights are used extensively on Cempedak, typically with a diameter of around 20cm and with greater tensile strength than steel.

As strong as steel

Perhaps one of the most extraordinary features of the resort construction, which is not appreciated until you see it for yourself, is the bathroom floor on the second level of each villa. It is a large slab of concrete and stone – that weighs nearly two tonnes – supported by bamboo beams alone. There are no steel supports.

You are also reminded that bamboo is, in fact, a grass and one of its key benefits is that you do not kill the plant when you cut it down. It simply sends up a new shoot. Bamboo is also a fast grower with some species able to grow up to nearly 1m in a day.

The large bamboo pieces used in this project were at least four years old at the time and around 14m long. These unique properties make bamboo one of the most sustainable building materials in the world, Andrew likes to remind us.

Treatment for bamboo

One of the weaknesses of bamboo is that it does not like to get wet or get too much direct sun exposure. It likes to have an ‘umbrella’ to keep the rain off and boots to keep its feet off the ground. For this reason, you will notice that the uprights are typically supported on stone footings.

Another weakness is that there a number of insects who like to eat its fibrous structure. The most common of these insects is the ‘post powder beetle’ which bores into the upright to lays its eggs. The best treatment for bamboo is to soak the bamboo in a solution of borax, a naturally occurring mineral and not dangerous for humans.

Explaining different techniques

One of the things that makes bamboo special is the curved shapes that can be created with the material. To form these shapes, bamboo is split and then rebound together to form long lengths that are then reformed and tied to the uprights to get the wonderful curves you see on all of our buildings. These are called Lidi. The ridge line on your villa is formed with a single piece of this measuring 43m and weighing approximately 500 kg.

About 90 pieces of the large petung bamboo, 500 pieces of the smaller rafter bamboo, and 500 metres of lidi were used in each villa. Approximately 50m2 of bamboo was used for flooring and 2800 strips of alang alang (atap or thatch) made up the roofing.

The flooring is a split bamboo 5cm wide, nestled together, then pressed and pinned with long bamboo pegs. These are then secured to the flooring members using bamboo pegs.

Because bamboo does not like to get wet, a recycled rubber wood was used for any outdoor flooring or decking. This material if made from veneer taken from rubber trees that have passed their useful life.

In keeping with trying to minimise any man-made materials, most of the furniture was created using recycled teak, commissioned by the interior designers. But you will notice that some items of furniture – particularly the distinctive round lounge coffee table – makes good use of bamboo in a novel fashion.

Drinking in the Dodo Bar

Perhaps one of the most unique buildings on the Cempedak Island is the Dodo bar. Architect/designer Chiko was inspired by a conical shaped shell that is found on the beach and a desire to use the naturally black bamboo species that is found on his home town of Bali.

In the bar, is a taxidermist’s interpretation of what a Dodo would have looked like. There are no intact original Dodo’s in the world only skeletons. Andrew recalls that the last Dodo skeleton to sell fetched $1million at auction: “A little out of our budget!”

The transition from building to operations

Asked what happened to the project team, the master developer/owner Andrew Dixon proudly tells me that many of the key ‘bamboo builders’ were offered jobs after Cempedak was completed and they continue to work on the island. Some of them have now been working on the island for seven years or more.

To help staff transition to the operational side of the resort, a teacher was hired and sent to Cempedak once a week to give English and first aid lessons to the project staff. The original Balinese construction team were also generous in teaching them many of the construction techniques used in the build. This helped give them confidence, Andrew insists, and they are now important members of the staffing team who know the island better than anyone.

In undertaking this ‘bamboo building tour’, it reminded me to the first big bamboo construction I visited years ago – The Green School in Bali way back in 2010. I also referred to Bamboo as the Ultimate Sustainable Material and the article by Paul Miles in the UK Financial Times I 2007.

Here’s a link to the World Economic Forum’s article on sustainable green buildings, which included Bali’s Green School. Read more about the community-based effort that aims to improve Indonesia’s ability to use and manage bamboo sustainably, called 1000 Bamboo Villages, which started in 2015.

- Photo credits: Cempadek Private Island and M Hickson.