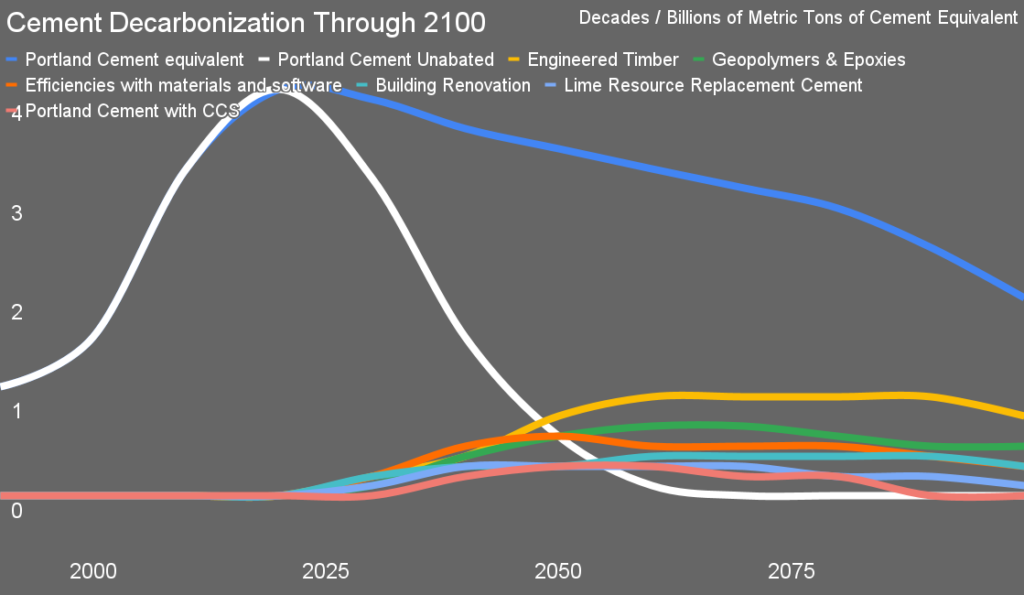

Global cement, responsible for fueling massive infrastructure projects in the West and, most recently, China, is about to enter long-term decline, with mass timber as well as geopolymers, epoxies and improved material software, fuelling the next wave of construction.

That is according to Michael Barnard, a climate futurist, strategist, and author who has published ‘Cement Displacement and Decarbonization through 2100,’ projecting the decade-by-decade change to the building and construction market over the next 75 years. Mr Banard is the Chief Strategist for the TFIE (The Future is Electric), consulting to billion-dollar hedge funds and multinationals – and yesterday, he presented his findings to the Indian Smart Grid Forum.

And the report findings are clear: the global demand for Portland Cement, starting from 2030, will experience a rapid and continuous decline – with shrinking demand for mega projects, coupled with the increasing cost from carbon pricing and regulations making Portland Cement uncompetitive: “If it were three times as expensive or limestone weren’t ubiquitous, we would be using existing alternatives, which are usually lighter and leaner for the same structural virtues,” Mr Barnard said.

“You’ll note that it’s starting to decline in this projection, slightly by 2030 and more steeply in coming years,” he said, due to several reasons: “First is that cement demand fell in the West from 1990 to 2020 as those affluent regions had already built most of their infrastructure and urban areas by that time,” with “the vast majority of the growth was in China, as with everything else.”

In April, Wood Central reported that 25% of China’s cost is now sinking under the weight of its concrete, steel and glazing mega projects – “China did in 40 years what took the West 80 to 150 years, and is now reaching the end game of building cities and infrastructure,” according to Mr Barnard.

“India, Brazil, Indonesia, and Africa don’t have the conditions that will lead to the mad dash of the (steel-and-concrete) building that China experienced,” he said, adding that “their demand growth will be slower and spread over the next 150 years.”

Mass Timber is the big winner in the wake of Cement Displacement.

Last year, Wood Central reported that the UN’s new Construction Blueprint was pushing to replace carbon-intensive building materials, like steel and concrete, with bio-based materials like timber, bamboo, and biomass, saving emissions up to 40% by 2050.

Already, researchers in the United States, Canada, and Australia are projecting massive increases in mass timber consumption, with global governments incentivising timber and timber-steel hybrid systems as they pivot to meet net-zero targets.

“With the rise in the cost of cement and the demand reduction, the alternatives spring into action,” Mr Barnard said, “in my assessment, the largest of these is likely to be engineered timber,” adding that “structural strength is equal to reinforced concrete with a fifth the mass. Every ton of engineered timber displaces 4.8 tons of reinforced concrete, hence the roughly 0.5 tons of cement required for the concrete.”

Mr Barnard said the key is not to increase forest harvesting but to create higher-value timber products, such as cross-laminated timber, glulam, and laminated veneer lumber: “We harvest roughly 3.5 billion cubic meters of wood annually. Much of that goes to single-use products, from chopsticks to tissues to paper towels.”

“We harvest so much that we can displace an enormous amount of cement and contract simply by diverting just a subset of single-use wood and paper products to engineered timber,” he said.

“The developed world has massive forestry industries, the developing world has massive forests,” Mr Barnard said, with China’s Great Green Wall showing the potential for reforestation and afforestation to create a sustainable forest industry, where an industry barely existed before 1980.

“A decarbonised forestry industry that expands forest cover and harvests a subset of mature trees annually for carbon dioxide sequestration, first in buildings and then in long-term sequestration pathways, will be a key part of our future.”

- To learn more about Mr Barnard’s work, read the full presentation at Clean Technica.