From October 2023, NSW architects and developers must measure embodied carbon in their designs.

The requirements are part of the new Sustainable Buildings State Environment Policy, a shift from energy emissions to reducing embodied carbon.

The push to measure embodied carbon is part of a global push towards Scope 3 emissions – indirect carbon and greenhouse gas emissions from an organisation’s supply chain.

In the case of construction, this could include the embodied carbon from the production and transport of concrete, steel, and timber.

In Australia, MECLA (the Materials and Embodied Carbon Leaders Alliance) has committed to reducing scope 3 emissions by 12.% to 25% by 2030 with a 1MT/year reduction in scope 3 materials by 2030.

Funded by the NSW and South Australian State Governments, MECLA is managed by WWF, Presync, and Climate-KIC Australia and has a dedicated Engineered Timber working group (5f).

According to Associate Professor Phillip Oldfield, the University of NSW Head of Built Environment, “timber is a great choice, as it is effectively the anti-concrete.”

Speaking to Climate Control News, Dr Oldfield cited recent research which has shown that by increasing the use of timber up to 30 per cent of all new multi-storey buildings by 2050, Australia can get the built environment down to zero emissions.

Dr Oldfield strongly supports the new policy and said developers must provide healthy, comfortable, safe and sustainable places for people to live, work and play.

“Every square metre we build has a carbon footprint, which can be quite high because the materials we rely on to construct buildings are very carbon intensive.”

The challenge for the building industry, he said, is to adapt future regulations to focus on embodied emissions rather than operating emissions.

“Any new building constructed in Australia today, we expect at least half of its total carbon footprint over its life will be embodied carbon, possibly even more.”

The World Green Buildings Council (WGBC) is pushing for all new buildings to be net zero operationally by 2030 – a plan with the strong backing of the Green Building Council of Australia.

Effectively, the carbon footprint for the buildings of the future will be all about embodied carbon.

The key for the next generation of architecture is to shift away from new buildings and think about reuse and redesign.

“Keeping the structure and becoming increasingly creative about building around it is a design strategy with big CO2 savings,” Oldfield explained.

He cites the Paris 2024 Olympic Games – where 95% of the venues and infrastructure use existing venues, retrofitting and temporary buildings.

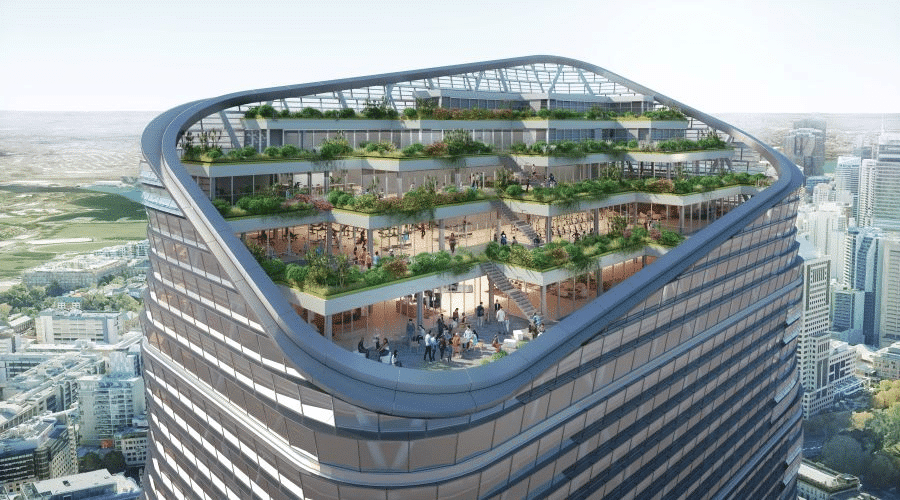

An example closer to home is the upcycling of the Quay Quarter Tower in Sydney.

In April, Wood Central contributor Mark Thomson reported that the expanded 1970s office tower had been extensively recycled and transformed. The new building repurposes the former AMP Centre at 50 Bridge Street, initially designed by Peddle Thorp and Walker and built in 1976.

“Two-thirds of the beams, columns, floor slabs, and almost the entire core built has been retained,” Mr Thomson said.

This saved almost 12,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide compared to complete demolition and conventional new construction tons.

Another way to reduce embodied carbon, Dr Oldfield said, is to build smaller and use low-carbon materials.

“Medium-density housing and apartments tend to be smaller, more compact and often share amenity and infrastructure, all of which reduces embodied carbon,” Dr Oldfield said.

“Replacing carbon-intensive materials such as steel and concrete with lower carbon equivalents is important for reducing embodied carbon.”

Using biomaterials like timber, bamboo, straw, cork, and even hemp leads to lower overall embodied carbon, as they use less energy to create and store carbon absorbed during their growth.

Finally, the building and construction industry can dematerialise.

The structural steel used in 19th-century buildings was delicate and thin compared to today’s structures.

At that time, materials were expensive, but labour was cheap, so it made economic sense to design in this way.

However, that is changing with the AI and Automation changing the paradigm.

“Innovations such as 3D concrete printing are already being used to minimise the amount of concrete in some buildings. A recent innovation has been the redesign of concrete beams,” Dr Oldfield said.

“Think less is more in everything from the structure of a building to finishes and fixtures.

“For example, instead of suspended ceilings, no ceiling and exposed beams. Instead of carpets, which need to be replaced every ten years, have polished floors. It’s about questioning whether you need every material in the first place.”