A Japanese gentleman of obvious means says Ferraris are his ichiban, his highest rating for motor cars.

“I just love them,” says the industrialist with a passion.

But love can be blind – koi wa moumoku – or can it?

Mister Haruto – I think I got the name right – has a few ‘rampant Italian stallions’ inside his garage in Chiba, not far from Japan’s Mount Fuji.

‘Garage’ is an inept description; it’s rather, as the owner and architect prefer, ‘The Big Circus Tent’, and it’s fitted out with an array of engineered native timbers to match the opulence of the cars parked inside it.

But back to Mister Haruto’s preference for Italian Ferraris. Why not Japanese brands such as Nissan, Toyota, Mitsubishi … and the super-expensive Lexus? Where do his loyalties lie?

What about the 2023 Drive’s Car of the Year, the $47,390 Nissan Qashqai? Or the Lexus LFA Nürburgring, which sells at a mere $215,000?

Yes, apart for the affection, it’s the price and prestige that seems to matter.

Under the Circus Tent we spotted two special Ferraris – a $US Monza SP2 at $US1.8 milllion and a Pininfarina Sergio, the most expensive in the Ferrari range, at $US3 million.

While we come to grips with these dizzying numbers, let’s go back under the Big Circus Tent.

“Spending [an appropriate word] time” with cars is the central idea behind this holiday residence designed by Hitoshi Saruta, an architect at the Tokyo-based Cubo Design Studio. “An enjoyable sanctuary for a car loving client and their friends”.

Unlike a traditional home featuring an attached garage, the objective here was to create a seamless connection between individuals, automobiles, and living spaces in a laid-back setting across 313 square metres.

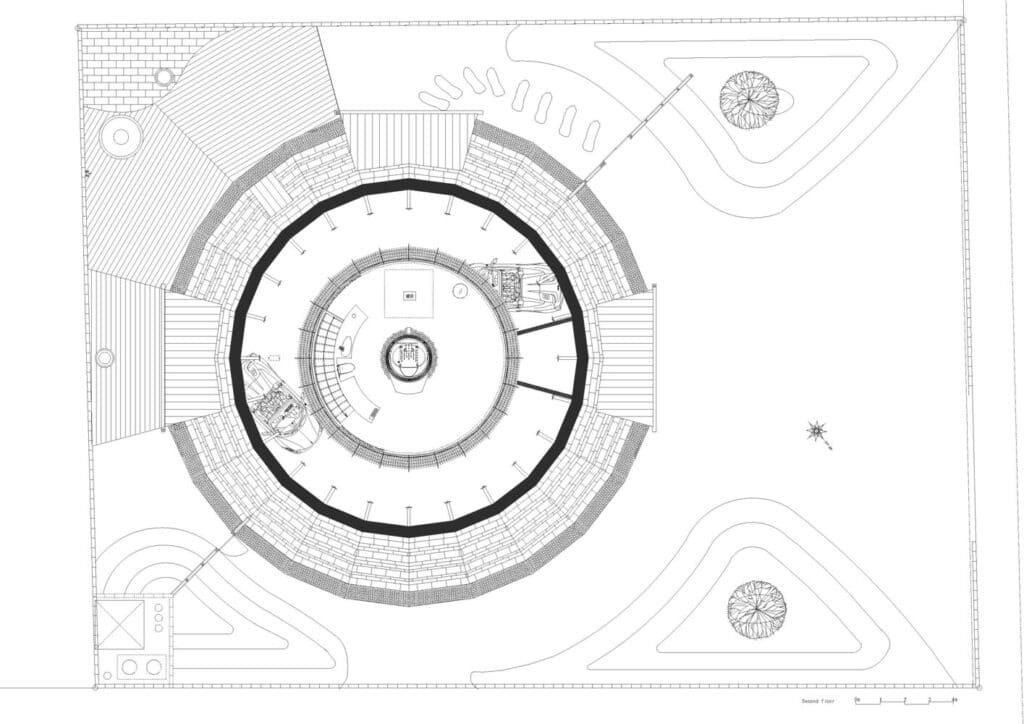

The client’s wish for a versatile home that could be effortlessly adapted for multiple purposes led to the development of a circular layout. This design, which lacks dead ends and allows for free movement of both people and cars throughout the ground floor, supports various configurations while embodying the ‘unconventionality’ often desired in holiday homes.

Drawing inspiration from a circus big top, the striking yet straightforward structure consists of a substantial 24-sided volume and a separate round-table-like volume that constitutes the second storey. The core that underpins the tent-like construction is sans columns, relying instead on the stability provided by angled external walls.

To keep expenses to a minimum (should Mister Haruto worry), the structure employs standard building materials, while cutting-edge pre-cut timber technology and high-precision steel hardware manufacturing techniques facilitate the unique shape.

The ground floor functions as a ‘garage living’ space shared by both people and motor cars with essential features concentrated in the core and outer perimeter. The upper level serves as a private area, housing the owner’s bedroom and a central hot tub complete with a cascading shower.

When viewed from below, the dwelling’s framework calls to mind an unfolded paper parasol, a deliberate nod to Japanese aesthetics. The client’s playful nature led to the incorporation of numerous entertaining elements throughout the residence, making it a lively gathering place for automobile aficionados on weekends.

“Reminiscent of an adult version of the clandestine forts that we erected on vacant plots as children, the project was as enjoyable to conceive as it is to reside,” Hitoshi Saruta enthused.

Construction timbers were chosen from native species such as Japanese red pine and cypress.

Earlier this month, Wood Central reported on the grow of wooden buildings in Japan – supported by a policy to use timber in buildings since 2010. As cross-laminated timber is one of those engineered timber products, the amount of CLT production has been increasing in Japan under this policy.

The purpose of this was to produce generic life-cycle assessment data for CLT production in Japan and to propose measures for reducing environmental impacts of CLT production.

‘The Big Circus Tent’s’ boundary is from material production to CLT production.

Traditional Japanese houses have boundless appeal for their elegant shapes and how they seamlessly integrate with their surroundings. Over centuries, craftsmen developed advanced woodworking techniques. Incredibly, a large portion of traditional Japanese buildings that exist currently have stood for hundreds of years, and the oldest wooden building in the world still stands in Nara, outside of Osaka.

Earthquakes, floods and lack of space are all environmental elements that Japanese builders have mastered. Japan is a highly forested region with difficult terrain, so it’s almost essential that building materials are mostly timber.

Japanese craftsmen took time to understand wood and its properties, taking advantage of difference in variation to make the strongest building material possible. Sustainability was an intrinsic part of construction, and daily life overall. Buddhist and Shinto traditions insisted on a strong connection to nature, ensuring nothing more than necessary was used, and the form of the materials are respected.

Timber posts are connected at right angles, using advanced joinery techniques. Wood is cut precisely to create complicated mortise-and-tenon joints, with wooden pegs used to keep it in place.

This wood joining technique and lack of metal allows the structure to be extremely flexible, giving it strong resistance to earthquakes and allows it to expand in wet conditions.

Another benefit of this method was that it is ‘reversible’, meaning individual elements can be taken out and replaced quickly, making repair simple and easy. They were often raised several metres off the ground to allow for ventilation.

• Orson Whiels tests the Drive Car of the year the Nissan Qashqai in Wood Central’s motoring column.