Developers in New England and across the American Northeast are at the forefront of a new trend in construction – with many turning to mass timber construction systems to build the next generation of low-rise and mid-rise housing stock.

Over the past two years alone, the number of cross-laminated timber buildings under construction has grown 168%, which has seen New York City, Boston, and even Havard University embrace the new green shift.

“The environment is causing us to [do this],” according to Jeff Spiritos, a New York-based developer who has, for the last five years, been eyeing mass timber construction, adding that “the affordability crisis is a mandate, and when you put them two together, you’re getting to the system of mass timber being worth a real second look.”

Mr Spiritos, who spent 25 years as a senior executive at real estate giant Hines Commercial Real Estate, is currently working on several mass timber builds across the region and spoke to local media yesterday from the ACME timber lofts, a remodelled furniture factory-turned apartment block in New Haven Connecticut.

“So here we are, let’s come into the bedroom,” Mr Spiritos said, pointing to the exposed walls and ceilings made from SFI-certified yellow pine harvested in Alabama. The gaps between wood are natural, and we’re not trying to hide the fact that it’s natural wood.”

According to a report published by Wood Central last month, the market for mass timber buildings in the Northeast—which includes New England, New York State, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania—is expected to surge, primarily fuelled by policymakers’ push to invest in seven-storey and higher multi-home residential construction.

However, until now, only timber species from the south, the Pacific West, and outside the country can be used in cross-laminated timbers. To date, just 74 of 2000 nationwide projects are located in the New England area – with “no CLT manufacturing facilities east of Chicago…and only one glulam manufacturer in New York State,” according to a separate report.

This has led the US government, through the USDA Forest Service, to invest in new research “to jumpstart the development of mass timber manufacturing in the northeast by using local softwoods.”

According to Amanda Smith, a researcher specialising in buildings for the nonprofit Project Drawdown, timber-based walls and beams can supercharge the region’s commitment to meet climate commitments.

“It’s important to look into the forestry practices of where you’re sourcing that mass timber from. But it’s maybe our best hope for reducing our use of concrete and steel,” Ms Smith said.

It may not be easy to replace carbon and steel in the tallest skyscrapers, but mass timber buildings are getting taller, according to Ricky McLain, who works with the Wood Works Products Council.

He said that thanks to a 2021 building code change, mass timber buildings can now rise 18 stories high, and “in those taller buildings, they’re nearly all multifamily for mass timber.”

“So then, I think what that did was open people’s eyes to see, ‘Okay, mass timber can be used in multifamily, and it does work well in multifamily.’

However, Mr McLain sees several roadblocks to greater adoption across the Northeast. Mass timber, he said, often has a more significant upfront cost, given that the majority of wood used in the systems is shipped from the southern states, Canada and Europe.

“It’s very difficult to convince a private developer who is maybe trying to do an affordable housing project, and costs are extremely, extremely important,” he said, adding that for costs to go down, it would require more suppliers and mass timber constructions.

Adding that the suppliers looking to enter the market want to see that the demand is already here, “they don’t want to hear there’s interest; they want to see that there are real projects. So, it’s a chicken and egg problem.”

Where mass timber can be cheaper is in labour costs. Mr McLain said mass timber projects typically need between six and ten workers, a fraction of the number used in steel and concrete constructions. “The fact that you’re needing that much fewer labour laborers on site is beneficial in sites where there’s not that much availability of labour.”

According to Chad Oliver, a professor emeritus at the Yale School of Forestry, building a mass timber industry in New England would be a “triple win” for the climate, biodiversity, and the industry.

“We have better biodiversity,” Oliver said. “We have less fire and CO2 pollution from fires and less CO2 pollution from building things out of steel and concrete.” For Professor Oliver, the biggest challenge facing mass timber in New England is that it’s still new here. “If more people understood the benefits, it would be more utilised in housing developments.”

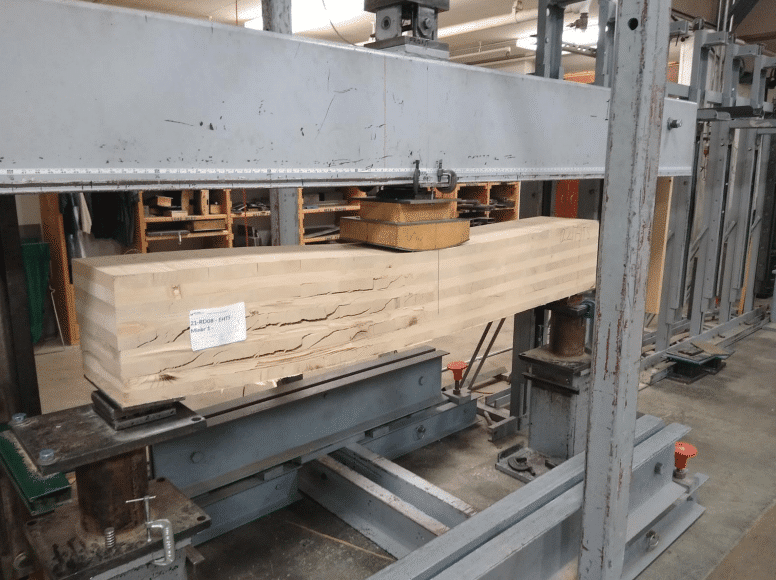

That’s why a new project, known as the Eastern Hemlock Cross Laminated Timber Certification and Demonstration Project, could break down several regional growth barriers.

Supervised by Dr Peffi Clouston, a Wood Mechanics and Timber Engineering Professor at the University of Massachusetts, “functionally, this is the first time that builders can call a manufacturer and order CLT panels made from Eastern Hemlock,” according to Charlie Levesque, the Executive Director of North East State Foresters Association. Before adding that this is the “first example of a Spruce-Pine-Fir cross-laminated timber from the Northeast.”

Dr Clouston noted that architects, builders and developers had shown a preference for eastern hemlock over spruce-fir, adding that “one architect said that compared to the very light and indistinct spruce-fir and the very yellow, hard look of southern yellow pine, eastern hemlock had a warmer, darker and richer tone.”

“Will this aesthetic preference continue and is strong enough to warrant a price premium over spruce-fir and yellow southern pine? It is too early to know.” However, “over time, as the market and supply chain matures, many barriers should be mitigated, and costs should come down.”