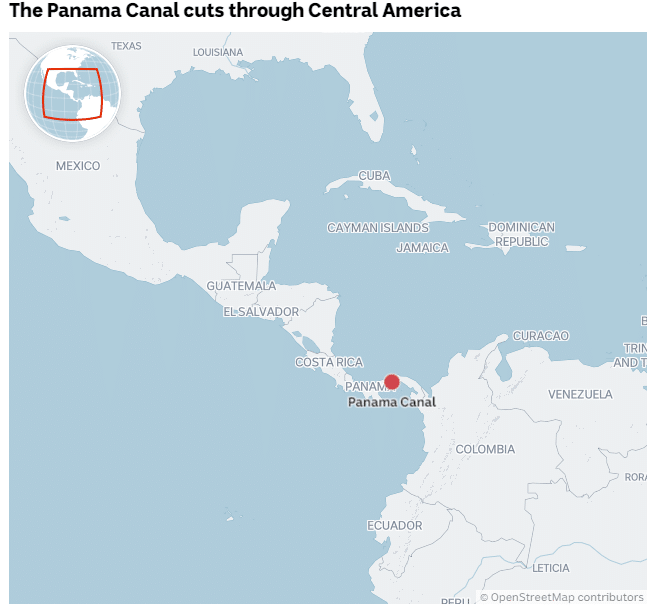

The Panama Canal, the century-old engineering marvel that revolutionised global trade, has been squeezed shut by drought, forcing shippers worldwide to face a painful choice.

They can wait in line for days or weeks as low water levels limit the number of ships passing through the 82-km waterway, carrying motor vehicles, petroleum, grains, coal and wood products.

Or they can pay millions of dollars to jump ahead of the queue if a ship with a booked reservation drops out. They can also sail away from an entire continent, sending their ships around the southern tip of Africa and South America.

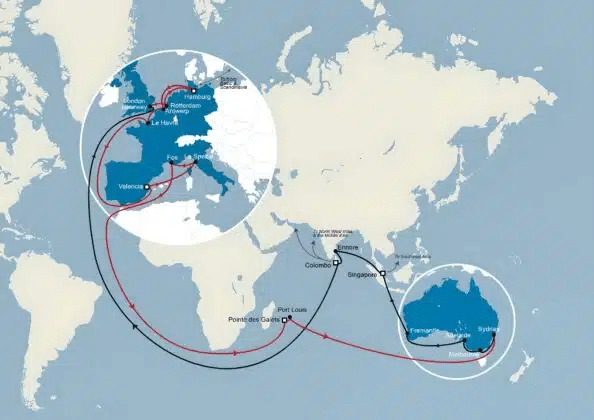

On the home front, other than an expected delayed passage through the Canal of Glacial Oak from US East Coast ports, China, the world’s biggest global supplier of plywood and other engineered wood products, follows a different route, allowing massive supplies to dominate markets in Australia and New Zealand.

The Canal moves about US $270 billion worth of cargo annually. It’s the trade route taken by 40% of all US container traffic alone and handles about 5% of all global maritime trade.

The Canal is also a vital component of the US freight transportation system. In 2023, the Panama Canal Authority reported that US East Coast ports exported 125.6 million long tonnes of cargo through the Canal, with 64% destined for Asia, while importing 61.1 million long tonnes of freight, with 68% originating from Asia.

Along the Gulf Coast, US $8.9 billion of agriculture products were exported from New Orleans and Baton Rouge ports to Asia in 2023-4. In addition, US west coast ports exported three million long tonnes of cargo via the Panama Canal, with 76% slated for Europe, while importing 6.4 million long tonnes of freight, with 49% originating in Europe.

Last October, Panama received 41% less rainfall than usual, leading to the driest October in 70 years in what was supposed to be Panama’s rainy season, bringing the Panama Canal Authority to restrict the number of ships that could pass each day.

A geopolitical tug-of-war between East and West…

But now the Panama Canal is turning into a geopolitical flashpoint with nothing to do with the weather. Its three most significant users are Japan, China and the US, which ceded the waterway to Panama in 1999 on condition that it remained politically neutral “with fair access to all nations and non-discriminatory tolls”.

The US is the origin or destination of 72.5% of all ships crossing the Canal. China is second, with 22.1%, and Japan follows closely with 14.7%.

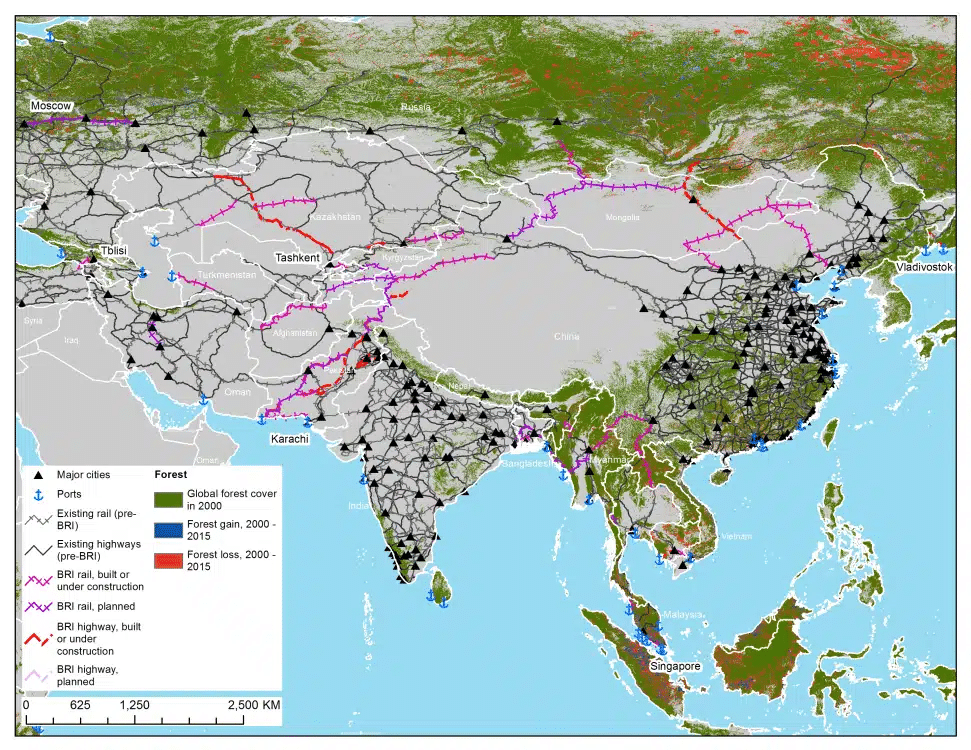

But China, which ships thousands of containers to Australia, New Zealand and other Pacific countries, exerts much tighter control over the waterway through its Belt and Road strategy.

China-linked companies now own significant port concessions at both ends of the Canal following the previous Panama government’s recognition of China’s claims on Taiwan, and this involves other deals, such as the construction of a new bridge.

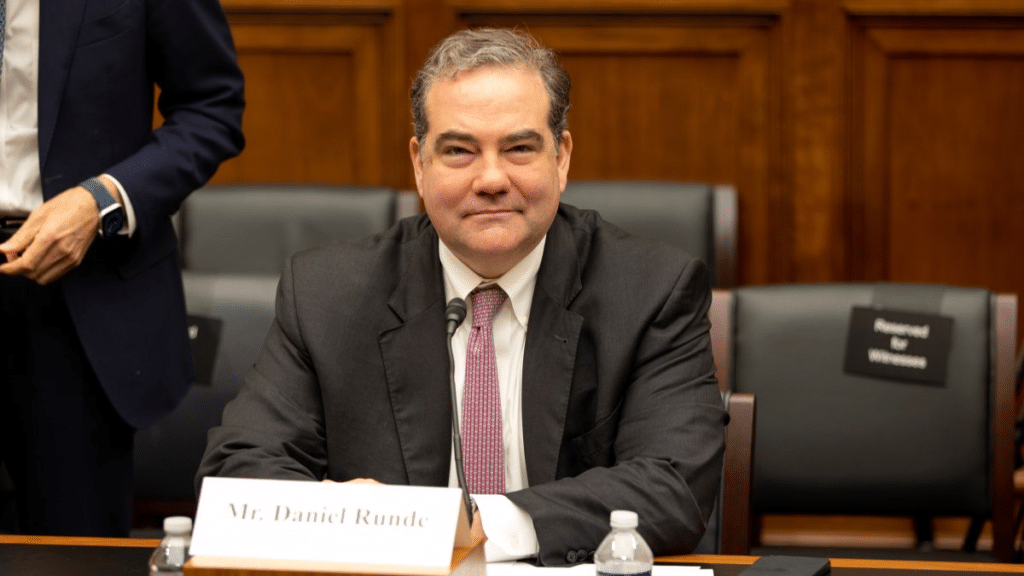

Backing up recent appeals by the US military, the Centre for Strategic and International Studies global analyst Daniel Runde warns that America needs to counteract China’s influence “before it’s too late”.

“The integration of the Panama Canal into a broader Central America strategy will require increased US engagement with Panama itself, with the added benefit of rivalling China not only in the canal but in the broader region,” Mr Runde said.

Even when the rains return, the issue of political neutrality will remain. As the terrorist-hit Red Sea slows, the geopolitical importance of these so-called choke points in world trade comes to the fore once again.

The disruption inevitably works its way through to the Asia Pacific…

In regular times, about 1000 ships navigated their cargo through the Canal, carrying some 40 million tonnes of goods – a lifeline for exporters and importers. It can reduce the sailing distance from the Atlantic to the Pacific and vice versa by a vast 8000 nautical miles (or 14,816 km).

But times are far from normal. Water levels in the locks are at their lowest because of the severe drought, too shallow for many vessels to be floated. Even for ships that can get through, the canal authorities have no option but to slash the number of slots available progressively.

Since early February, capacity has been reduced to 24 slots daily, two-thirds the usual number. Some shipping companies are desperate to get vessels through, reportedly paying seven-figure sums for a slot. Inevitably, these costs will be passed down the supply chain.

Although the Suez Canal is more important for trade in and out of Oceania (the Europe-Mediterranean region is Australia’s second-biggest market after north-east and south-east Asia), the Panama Canal is still a vital conduit.

According to available Shipping Australia figures, 2,520,490 tonnes of Australia’s cargo went through the waterway last year.

Meanwhile, shipping lines are still avoiding the Suez Canal despite a peacekeeping fleet in the Red Sea – leading European exporters and Australian importers to warn of supply shortages and price hikes at the port.

The attacks by the Houthi militia quickly caused the diversion of most of the container and other traffic away from the Canal, which in good times saw the transit of 12% of global trade, worth around a trillion dollars a year.

The biggest shipping companies, such as Maersk, Hapag Lloyd and MSC, promptly sent their vessels around Africa’s Cape of Good Hope, which extended the voyage by up to two often extremely rough weeks of sailing.

This raises fuel and operating costs and causes delays. Insurers immediately doubled shipping’s war risk premiums.

“These vessels use the Panama Canal on the US-Asia trades,” explains Shipping Australia. If the disruptions continue, analysts predict significant increases in daily spot rates for these ships of up to US $200,000 daily, above mid-December rates of US $48,000 daily.

Fortunately, the problems in the Panama Canal coincide with reasonably benign commercial conditions. Shipping Australia statistics show that freight rates are comparatively low, availability of ships is high, cargo demand is also relatively low, and fuel prices moderate, currently about US $600 per tonne using very low sulphur fuel oil compared with US $1100 in the past.

Inside the world’s largest and most arduous engineering project…

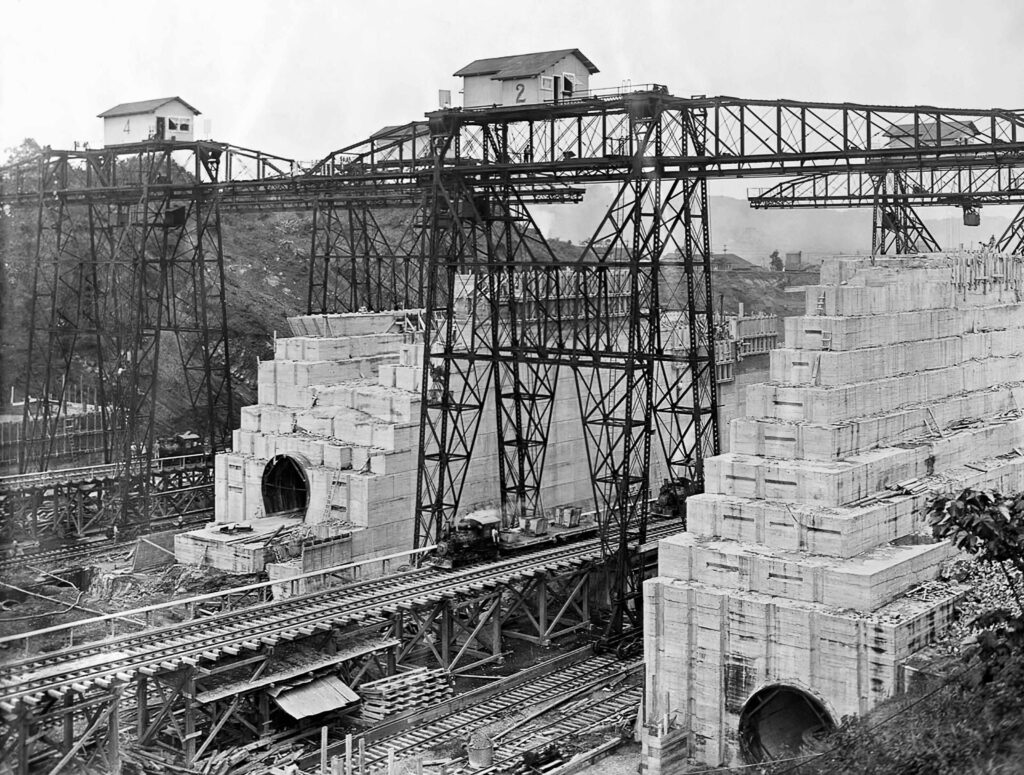

The Panama Canal, an artificial 82-km waterway that connects the Pacific Ocean with the Atlantic Ocean, was built between 1904 and 1914.

Canal locks at each end lift ships to Gatun Lake, an artificial freshwater lake 26 m above sea level. The shortcut dramatically reduces the time for ships to travel between the two oceans, enabling them to avoid the route around the southernmost tip of South America via the Drake Passage or Strait of Magellan.

An ancient hardwood forest’s vestiges tell how bad things are at the drought-stricken Canal. Gaunt tree stumps rise above the waterline just a few hundred metres from the massive tankers hauling goods across the globe.

They are all that remains of a woodland flooded more than a century ago to create the Canal. It’s not unusual to see them at the height of the dry season. But now, in the immediate aftermath of the rainy period, they should be fully submerged.

They are a visible reminder of how parched conditions have crippled a waterway that handles $270 billion a year in global trade – and there are no easy solutions.

The Panama Canal Authority is weighing potential fixes, including an artificial lake to pump water into the canal and cloud seeding to boost rainfall. Still, both options would take years to implement, if feasible.

With water levels languishing at 1.8 m below average, the canal authority capped the number of vessels that can cross.

To allow 24 vessels a day through the dry season, the Canal will release water from Lake Alajuela, a secondary reservoir. But these are short-term fixes. In the long term, the primary solution to chronic water shortages will be to dam up the Indio River and then drill a tunnel through a mountain to pipe fresh water 8 km into Lake Gatún, the Canal’s main reservoir.

The authority says the project and additional conservation measures will cost about $2 billion. It will take at least six years to dam up and fill the site. The US Army Corps of Engineers is conducting a feasibility study.

The Indio River reservoir would increase vessel traffic by 11 to 15 a day, enough to keep Panama’s top money-maker working at capacity while guaranteeing fresh water for Panama City, where developers have erected a ‘mini-Miami’ of gleaming skyscrapers over the past two decades.

The country will need to dam even more rivers to guarantee water through the end of the century. But moving the proposal forward won’t be easy. It will need congressional approval, and the thousands of farmers and ranchers whose lands would be flooded for the reservoir are already organising to oppose it.

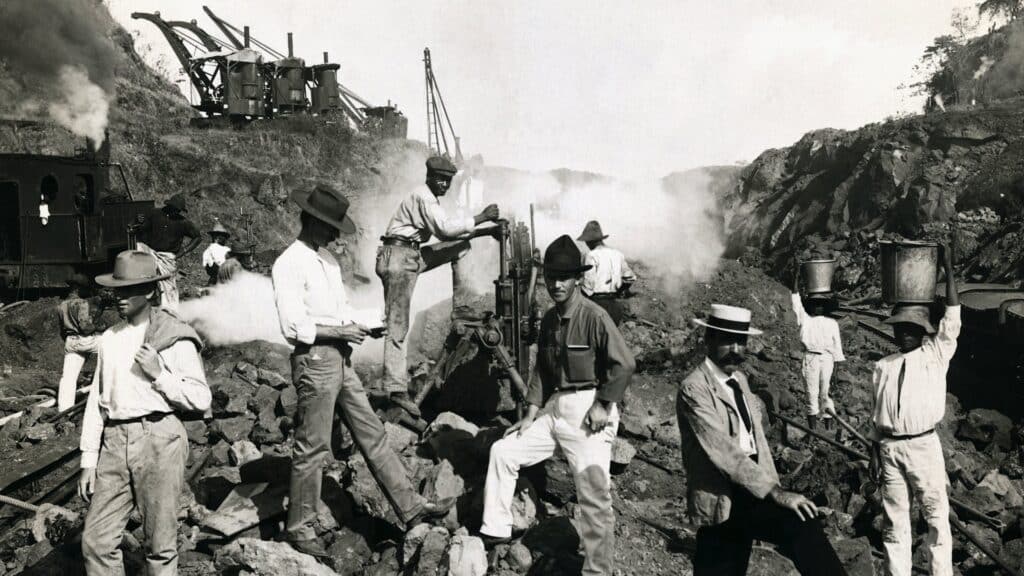

In a quest to fulfil a centuries-old dream to connect the two oceans, pioneer builders quickly learned that constructing a waterway across a narrow ribbon of land looked easier on a map than in reality.

The Panamanian isthmus proved to be one of the most difficult and deadly spots in the world to construct a channel. The builders of the passage attempted to re-engineer the natural landscape, but nature didn’t give up without a fight.

Construction crews had to move mountains in a snake-infested jungle with an average temperature of 30 deg. C and 2660 mm of rainfall a year. In the wet season, torrential downpours transformed the flood-prone Chagres River into raging rapids, soaking workers.

Sometimes, they didn’t see the sun for two straight weeks, and most mornings, they had to start work in damp clothing.

Death continually stalked the workers on the project site and could strike in many forms – either a rolling 18-tonne boulder or minuscule, malaria-carrying mosquitoes that bred by the millions in festering swamps and puddles.

Over more than three decades, between 25,000 and 30,000 workers died in the construction of the Canal while artificial limb makers clamoured for contracts with crippled survivors.

The total volume of excavations by French and American workers was a staggering 156,000,000 cubic metres. In 1913, during the building of the Panama Canal, US President Theodore Roosevelt created what was then the world’s largest artificial lake (Gutan) by damming the Chagres River and flooding an old-growth forest jungle the size of Montreal.

A century later, using submersible hydraulic chainsaws lubricated with vegetable oil, these perfectly preserved native tropical hardwood trees were harvested from that underwater jungle.

Those same promising native species – Byrsonima crassifolia, Dalbergia retusa, Dipteryx oleifera, Hyeronima alchorneoides, Platymiscium pinnatum and Terminalia Amazonia – are today being used as an enrichment contribution in plantations of non-native timber species such as teak (Tectona grandis).

Although large areas of the Panama Canal watershed have been converted to these teak plantations, they are not yet providing the hoped-for economic and ecological benefits of forest landscape restoration.